Introduction to this course

Overview

Teaching: 10 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

What is the purpose of this training?

Who are the target audience?

What will they learn at the end of this training?

Objectives

Describe the motivation, purpose, target audience and expected outcome of this training

Managing Open and Reproducible Computational Projects

Over the last decade, several tools, methods and training resources have been developed for early career researchers to learn about and apply data science skills in biomedicine. This is often referred to as biomedical data science, with the following definition.

Biosciences and biomedical researchers regularly combine mathematics and computational methods to interpret experimental data. The term “data science” describes expertise associated with taking (usually large) data sets and annotating, cleaning, organizing, storing, and analyzing them for the purposes of extracting knowledge. […] The terms “biomedical data science” and “biomedical data scientist” […] connote activities associated with the creation and application of methods to new and large sources of biological and medical data aimed at converting them into useful information and knowledge. They also connote technical activities that are data-intensive and require special skills in managing the large, noisy, and complex data typical of biology and medicine. They may also imply the application of these technologies in domains where their collaborators previously have not needed data-intensive computational approaches.

– Russ B. Altman and Michael Levitt (2018). Annual Review of Biomedical Data Science

In contrast to the definition above (and as will be explained in the next chapters), we think research which is not data intensive would also gain in applying data science principles. However, to ensure that data science approaches are appropriately applied in domain research, such as in biosciences, there is a need to also engage and educate scientific group leaders and researchers in project leadership roles on best practices. Computational methods might indeed be as complex as a neural network, but even statistical tests and producing figures for a publication require data science and coding methods.

Researcher use data science skills to apply computation techniques and reproducible data analyses approaches to their research questions. In order to apply these tools, researcher first need to understand and apply the building blocks of data science, especially research data management, collaborative working and project management.

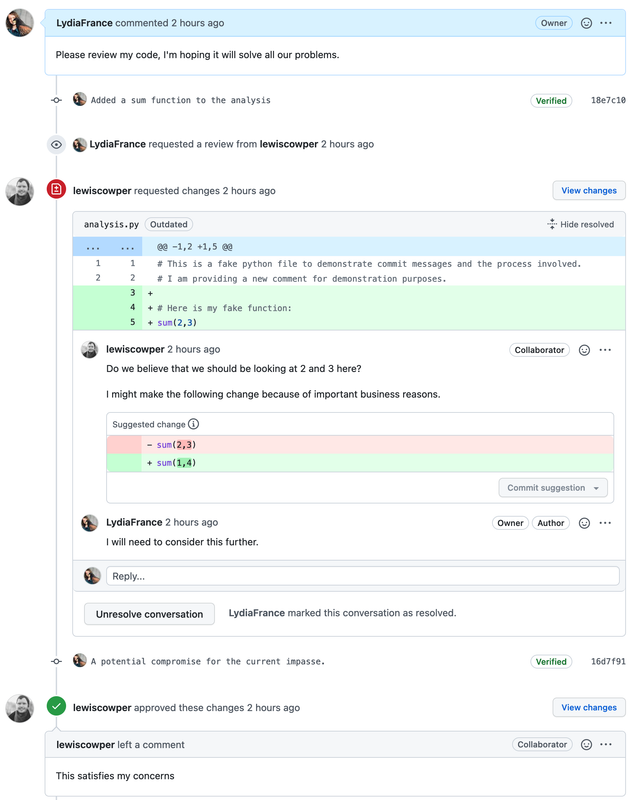

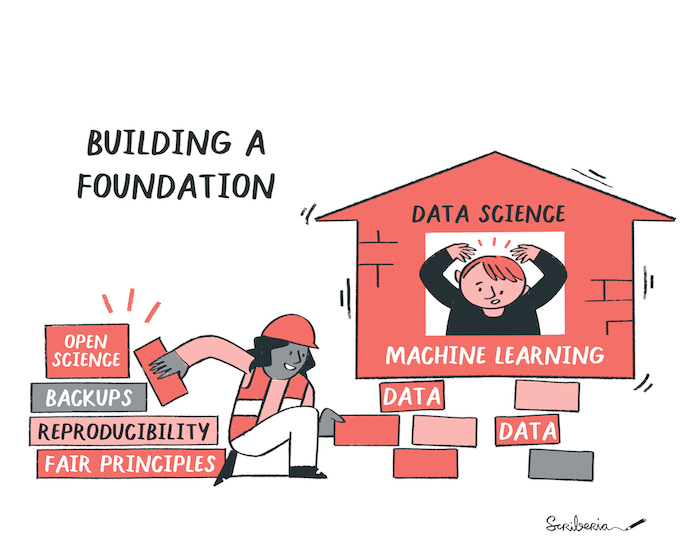

How to apply data science in biology. The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia for The Turing Way Community Shared under CC-BY 4.0 License. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3332807

In some instances, it has been argued that “data science” simply rebrands existing fields like statistics or computer science. Our view is that data science has gained traction as an overarching term due to increased data availability and complexity; development of computational methods; advances in computational infrastructure; growing concerns about scientific rigor and the reproducibility of research findings; and a recognition that new advances will result from interdisciplinary research and collaboration. These trends are not unique to data science, but their integration and consolidation under a single term, however broad, reflects an understanding of their interconnectedness and is a real shift in the scientific landscape

- Goldsmith, J., Sun, Y., Fried, L. P., Wing, J., Miller, G. W., & Berhane, K. (2021). The Emergence and Future of Public Health Data Science. Public Health Reviews, 42. doi: 10.3389/phrs.2021.1604023

With new technologies supporting the generation of large-scale data as well as successful applications of data science, Machine Learning (ML) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) in biomedicine and related fields have recently shown huge potential to transform the way we conduct research. Recent groundbreaking research utilising AI technologies in biomedicine has led to an enormous interest among researchers in data science, ML and AI approach to extract useful insights from big data, make new discoveries and address biological questions. As pictured below, in order to apply these tools, researcher first need to understand and apply the building blocks of data science, especially research data management, collaborative working and project management.

In what aspects of your projects do you already apply computational and statistical approaches? Do you consider data science relevant for your project? Why/Why not?

The Data Science for Biomedical Scientists project helps address this need in training by equipping experimental biomedical scientists with essential computational skills. In all the resources developed within this project, we consistently emphasise how computational and data science approaches can be applied while ensuring reproducibility, collaboration and transparent reporting.

The goal is to maintain the highest standards of research practice and integrity.

In this training material for learning how to manage computational projects, we discuss essential practices for computational reproducibility required for carrying out meaningful analyses of research datasets through data exploration, processing, visualisation and communication. We present unfamiliar and complex topics from computation and data science to biologists by providing examples and recommendations from their fields. The goal is to enable effective management and sharing of their computational projects. We therefore encourage you to go through this training material before taking our second workshop, more focused in AI and Data Science.

Jargon Busting

Below we provide a simple definition of some terms that we use in this project in the context of scientific research:

- Best Practices: Set of procedures that have been shown by research and experience to produce optimal results and that are established or proposed as a standard suitable for widespread adoption. Definition by Merriam Webster

- Data Science: An interdisciplinary scientific study that uses mathematics and computational tools to extract insights from big structured and unstructured data.

- Computational Project: Applying computer programming and data science skills to scientific research.

- Reproducibility: When the same analysis approach is applied to the same data, it should give the same answer - this answer should be reproduced by others using the same analysis and data originally used.

- Computational Reproducilibity: Reproducing the same result by analysing data using the same source code (in a computer programming language) for statistical analyses.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI): A branch of computer science concerned with building smart machines capable of performing tasks that typically require human intelligence. Definition by Builtin

- Machine Learning (ML): A subset of artificial intelligence that gives systems the ability to learn and optimize processes without having to be consistently programmed. Simply put, machine learning uses data, statistics and trial and error to “learn” a specific task without ever having to be specifically coded for the task. Definition by Builtin

Target audience

Experimental biologists and biomedical research communities, with a focus on two key professional/career groups:

- Group leaders without prior experience with Data Science and ML/AI - interested in understanding the potential additionality and application in their areas of expertise.

- Postdoc and lab scientists - next-generation senior leaders, who are interested in additionality, but also the group more likely to benefit from tools to equip them with the requirements to enable the integration of computational science into biosciences.

Targeted measures and opportunities can help build a better understanding of best practices from data science that can be effectively applied in research and supported by senior leaders. Senior leaders, in this context, can be academics or non-academics working in advisors, experts or supervisors roles in research projects who want to lead rigorous and impactful research through computational reproducibility, reusability and collaborative practices.

Learning Outcomes

At the end of this lesson (training material), attendees will gain a better understanding of:

- Acquiring the necessary/essential basic tools to produce good quality and reproducible computational projects, including AI/ML related

- designing computational projects using collaborative, reproducible and open science approaches

- examining challenges and potential pitfalls in applying best practices in Data Science

- identifying tools and practices required for managing specific kinds of computational projects

- applying a systematic framework introducing computational protocols in their groups as project leads and/or managers

Modular and Flexible Learning

We have adopted a modular format, covering a range of topics and integrating real-world examples that should engage mid-career and senior researchers. Most senior researchers can’t attend long workshops due to lack of time or don’t find technical training directly useful for managing their work. Therefore, the goal of this project is to provide an overview (without diving into technical details) of data science and AI/ML practices that could be relevant to life science domains and good practices for handling open reproducible computational data science.

We have designed multiple modular episodes covering topics across two overarching themes, that we refer to as “masterclasses” in this project:

- Managing and supervising computational Projects (THIS training material)

- Introduction to Data Science and AI for senior researchers

Each masterclass is supplemented with technical resources and learning opportunities that can be used by project supervisors or senior researchers in guiding the learning and application of skills by other researchers in their teams.

Do I need to know biology and AI/ML concepts for this training material?

The short answer is no!

Although the training materials are tailored to the biomedical sciences community, materials will be generally transferable and directly relevant for data science projects across different domains. You are not expected to have already learned about AI/ML to understand what we will discuss in this training material.

In this training material, we will discuss best practices for managing reproducible computational projects, regardless whether they include AI/ML components or not. The training material “Introduction to Data Science and AI for senior researchers” is developed in parallel under the same project that introduces data science, AI and related concepts in detail. Although those are helpful concepts, it is not required to go through that training material to understand the practices we discuss in this training material.

Both the materials discuss problems, solutions and examples from biomedical research and related fields to make our content relatable to our primary audience. However, the best practices are recommended and transferable across different disciplines.

Pre-requisites and Assumptions

In defining the scope of this project, we make the following assumptions about the learner groups, which can be considered pre-requisites for this training:

- Our learners have a good understanding of designing or contributing to a scientific project throughout its lifecycle

- They have identified a computational project with specific questions that will help them reflect on the skills, practices and technical concepts discussed in this training

- This training doesn’t cover the processes of designing a research proposal, managing grant/funding or evaluating ethical considerations for research. However, we assume that learners have a computational project in mind for which funding and research ethics have been approved and comprehensive documentation capturing this information is available to share with the research team.

- We also assume that the research team of any size is (either partially or fully) established, and hence, we will not discuss the recruitment of team members.

Mode of delivery

Each masterclass has been developed on separate repositories as standalone training materials but will be linked and cross-referenced for completeness. This modularity will allow researchers to dip in and out of the training materials and take advantage of a flexible self-paced learning format.

In the future, these masterclasses could be coupled with pre-recorded introduction and training videos (to be hosted on the Turing online learning platform and The Turing Way YouTube channel).

They can also be delivered by trainers and domain experts, who can mix and match lessons/episodes from across the two masterclasses and present them in an interactive workshop format.

Next Steps after this Training

After this masterclass we recommend our learners take these next steps:

- Go through the “Introduction to Data Science and AI for senior researchers” masterclass (if not already completed)

- Explore the set of resources provided at the end of each lesson for deeper dive into various technical topics required to learn or guide the application of Data and computational research best practices in real-world projects

- Establish connections with other training and training materials offered by The Alan Turing Institute, The Crick Institute, The Carpentries, The Turing Way and other projects/organisations involved in the maintenance and development of this training material

- Connect with other research communities and projects in open research, data science and AI that offers opportunities to develop/enhance technical skills

- Collaborate with domain experts such as librarians, research software engineers, community managers, statisticians or people with specialised skills in your organisation who can provide specific support in your project.

Funding and Collaboration

The first iteration of Data Science for Biomedical Scientists, was funded by The Alan Turing Institute’s AI for Science and Government (ASG) Research Programme from October 2021 to March 2022. The project will be further developed and maintained by the members of The Turing Way and Open Life Science community.

This project is previously an extension of The Crick-Turing Biomedical Data Science Awards that strongly indicated an urgent need to provide introductory resources for data science in bioscience researchers. This project extension will leverage strategic engagement between Turing’s data science community and Crick’s biosciences communities.

Pulling together existing training materials, infrastructure support and domain expertise from The Turing Way, The Carpentries, Open Life Science and the Turing ‘omics interest group, we will design and deliver a resource that is accessible and comprehensible for the biomedical and wet-lab biology researchers.

This project will build on two main focus areas of the Turing Institute’s AI for Science and Government research programmes: good data science practice; and effective communication to stakeholders. In building this project, we will integrate the Tools, practices and systems (TPS) Research Programme’s core values: build trustworthy systems; embed transparent reporting practices; promote inclusive interoperable design; maintain ethical integrity and encourage respectful co-creation.

License

All materials are developed online openly under CC-BY 4.0 License using The Carpentries training format and The Carpentries Incubator lesson infrastructure.

Key Points

This material is developed for mid-career and senior researchers in biomedical and biosciences fields.

This training aims to build a shared understanding and facilitate the integration of computational reproducibility in data science.

Better and faster research !

Overview

Teaching: 35 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

How does this training relate to your work?

What are the benefits of using data science skills?

What can go wrong with working on data/code?

What are the challenges for teams and management?

Are there procedures and protocols that can help?

Objectives

Understand how this training material will help your research (and career).

Your research project is a computational project.

As a researcher, you are likely to use some sort of computational tools to process, analyse, and visualise data. You are also likely to work on your project with other members of the lab, and the success of your work may well depend on your interactions with your peers. In that sense any research project can be defined as a collaborative, computational project.

We all may have dfferent research and data science expertise. The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia for The Turing Way Community Shared under CC-BY 4.0 License. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3332807

Why are you here

Discuss why you/learners are taking this course, what are the expectations. Does the expectations align with the relevance of data science and content of this course?

Contents of this training material introduces methods and concepts to manage individuals and teams working on any computational project, which in the current era is literally all research projects. It is not about learning how to write code, but building a foundational understanding for computational methods that could be applied to your research. Furthermore, this training will provide guidance for facilitating collaboration and data analysis using tools like research data management, version control or code review.

We acknowledge the data science knowledge will vary. Nonetheless, we believe that the data science skills you will learn in this training will make your research process better. In the following sections, we will detail what we mean by “better”.

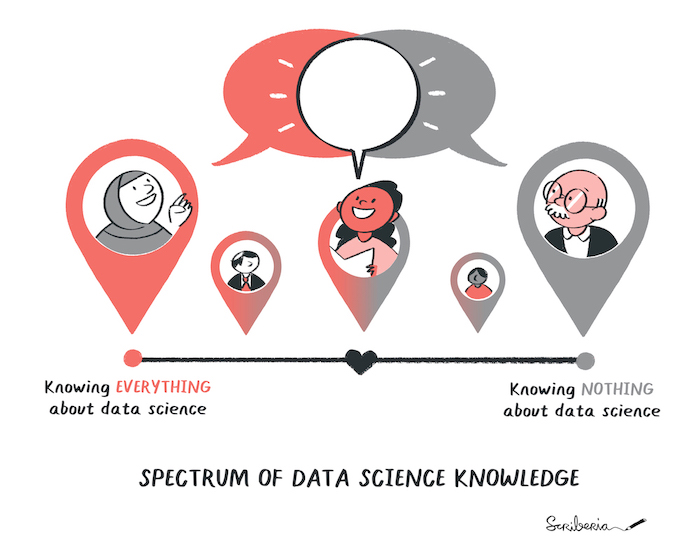

How data science will improve your research ?

Data science makes research flourish. The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia for The Turing Way Community Shared under CC-BY 4.0 License. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3332807

It is mostly about being efficient

Data science brings some structure in how data is collected, processed and analysed, making it easier to collaborate on a project, to publish extra research outputs and leveraging some extra potential your data may have. In the past, it helped me drive new hypotheses, detect problems with the research design early, and reduce the sample size needed to drive a solid conclusion. Eventually, it made my research more robust and trustworthy. But in the end, my real motivation is efficiency: very soon, the time I invested in learning and applying data science in my research was recovered multiple times when a manuscript had to be written (and re-written).

There are different ways to organise the different foreseen improvement, we decided here to start with improvement in the final result, improvement in the research process, and finally aspects of community building.

Using code for nicer paper

Powerful statistics

The most advanced statistical methods (like machine learning) are first developed in programming environment, and they are often difficult or impossible to implement in statistical software. In addition, some of the less advanced statistical methods requires intensive data processing that makes it very difficult to apply outside a coding environment.

Examples

- logarithmic.net/langevitour/2022-useR/#2 to explore orthonormal projections of high dimensional data.

- Results of water maze behavioural tests are better analysed using a survival analysis than an Analysis of variance (ANOVA). However, the data obtained via video analysis software is often not fitted for that analysis and needs to be transformed. Doing transformations by hand is time consuming and is likely to introduce errors.

Example’s references

- See Jahn-Eimermacher, A., Lasarzik, I., & Raber, J. (2011). Statistical analysis of latency outcomes in behavioral experiments. Behavioural Brain Research, 221(1), 271–275. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.03.007

- For water maze experiment analysis, see: Maugard, M., Doux, C., & Bonvento, G. (2019). A new statistical method to analyze Morris Water Maze data using Dirichlet distribution. F1000Research, 8(1601), 1601. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.20072.2.

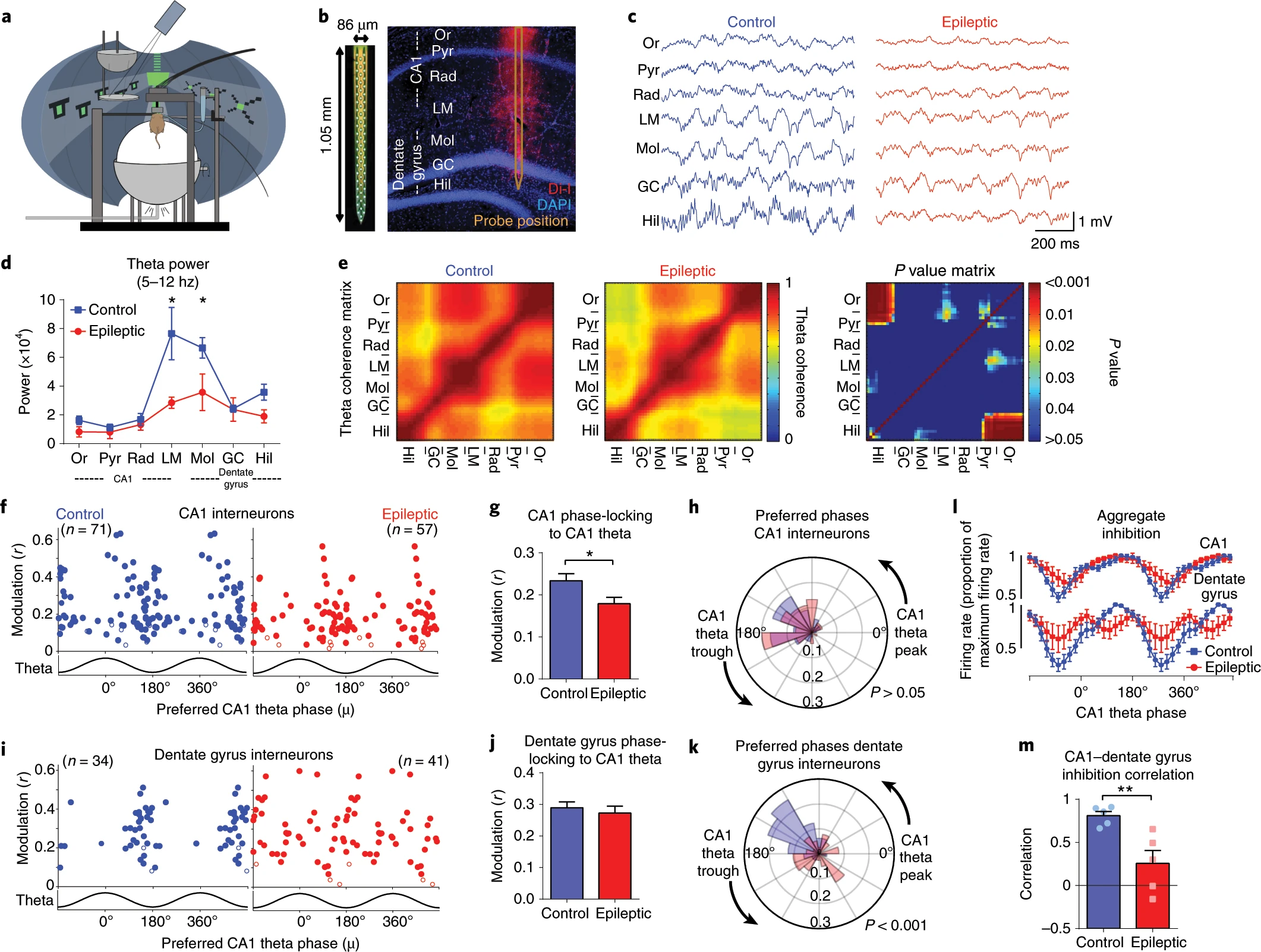

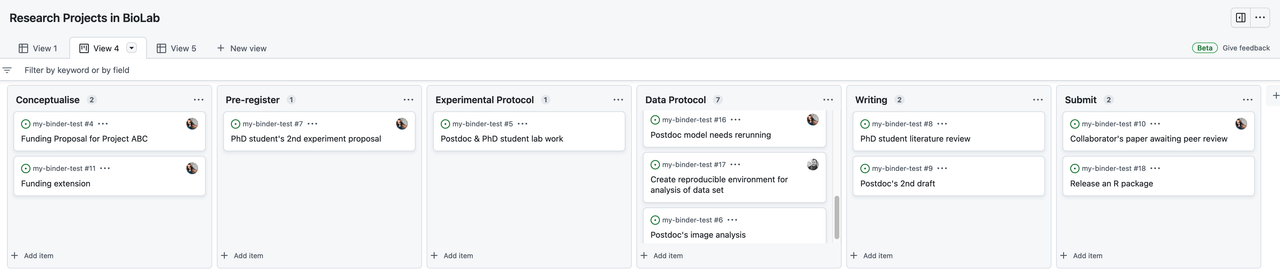

Informative (and inclusive) figures

Once you start using code for analysing your data, it will become much easier to do complex and informative visualisation. This often includes way to visualise and label single data points, or use visualisation on several dimensions (producing moving gifs of a 3D scatterplot for instance).

One can also automate the figure design choice, so that all figures look similar. Similarly, the production of several version of the same figure is very easy. For example, one can use different color pallette, one using the palette usually used in the field (the one your supervisor wants to see), and one for color-blind readers.

Single flights from different bees.

See a good example of data representation in differen format single flights from different bees shown in supplemnentary data: Menzel, R., Greggers, U., Smith, A., Berger, S., Brandt, R., Brunke, S., …Watzl, S. (2005). Honey bees navigate according to a map-like spatial memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(8), 3040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408550102

Reproducible analysis

Good scientific practices are aiming at securing the robustness and reproducibility of the scientific endeavour. As a researcher, assuring computational reproducibility of your results is a relatively easy step in making your research more robust.

What to expect in your reproducibility journey. The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia for The Turing Way Community Shared under CC-BY 4.0 License. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3332807

The reproducibility of an experiment not only requires a detailed description of the methods and reagents used, but also a detailed description of the analysis performed. The ultimate description of the analysis is to provide all elements necessary for reproducing the analysis (computational reproducibility). This includes the data and the code used to analyse it (in a form that can be reused in a different computational environment).

In practice, sometimes one may not be able to provide all elements openly (for instance, some medical data cannot be shared openly for privacy reasons) for everyone to be able to reproduce all the results. But co-workers (and maybe reviewers) should be able to reproduce the analysis (e.g., on anonymized data).

The emergence of reproducible reports is another aspect of computer reproducibility. Literate programming using Jupyter notebooks, Rmarkdown, stencila or quarto (tools that can usually use Python, R, or Julia) is indeed growing in popularity. These tools allow you to show data and analysis side by side, with written explanations and interactive visualisations. These outputs can not only be used as blog posts, or lab reports, but can also be published as an enhanced publication, a concept called executable research articles: https://gmaciocci.medium.com/list/the-evolution-of-executable-research-articles-823e42a9fa60

Diversifying research outputs

While the main recognition currency in academia is still (first) authorship in peer reviewed publication, new scientometrics are developed to recognize publication of other research outputs. In particular, datasets and software publication are officially reviewed in the evaluation of certain grant, for example for the Marie-curie european program. Data science principles will make it easier to publish datasets, software, reagents or hardware you are anyway producing during the research process.

By publishing datasets and code, you will not only help other researchers, but gain extra recognition for your work. However, open data and open code requires a specific documentation, which we will touch upon in this training.

Computational tools you produce in your lab can be released as open source software and credit will be given globally. This may also be true for hardware you design (this aspect will not be discussed in this training) or datasets you collect.

Improved Research Process

Data quality

Did you know that manually copy-pasting data is one of the primary source of data corruption ? Combining datasets or processing data (such as cleaning or transforming into different formats), can therefore be best achieved using code. The process is not only safer, but it is often faster.

Another underevaluated issue is the amount of data you will collect. The more data you have the more sophisticated tools and workflows you may need. It is also more likely that your data (or code) gets corrupted, mixed up, outdated, or lost. In particular, when something goes wrong during the experiment, code might be used to create warnings, so that the setup or protocol may be modified on the fly or between sessions.

Reproducibility and automation

While we already mentioned the advantage of reproducibile analysis for the quality of the research, we did not mention how useful this is during the research. With reproducible analysis, it is effortless to run a new dataset in the analysis workflow, it becomes possible to explore the data at a single experiment level, which may enable new hypotheses, or spot issues that were not foreseen in the experimental design. It makes also certain that difference in the figures are due to difference in the dataset, not any manual processing of the data one may have forgotten to docuzment.

Collaborative working

Within science teams, group work is critical for experimental design and implementation. In addition, there are rapid developments in how scientific results and methods are shared, and collaborations have never been more global or rapid. This means that several people will likely be working with the same data files.

Data science allows for the management of how one or multiple people work on the same project (as well as the same code). It requires different skillsets than those taught in traditional science courses or a typical coding class.

Who can add to your research?

Facilitating communication and sharing will make it easier for your colleagues to help you. Can you think of people who can help you in your research, directly in your lab or at your institution ? Would it help for them to have access to your data? How could they participate, and how can you give them credit?

Needs from the future you

It is very interesting to consider your future self as one collaborator in your project. Anything you may forget in the next three to five years should be documented, if you want your future self to be able to (re-)analyse the data you are collecting. Indeed, the advantage of working collaboratively in a project can indeed be translated directly in a project you drive mostly alone.

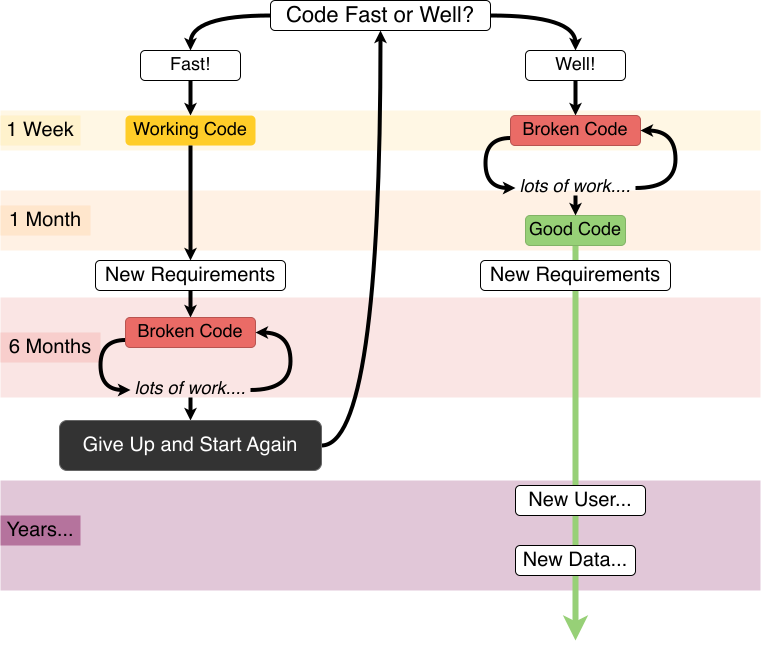

Efficiency

The time invested in your data and code will be paid multiple times by the efficiency improvement in your workflow, if that investment is done early in the project. Because one can consider your past self as one of your collaborator, the advantage of working collaboratively in a project can indeed be translated directly in a project you drive mostly alone.

At this point, you may be convinced that the extra work of designing your project using data science principles will be worth it. But here comes the best argument of all: in the end you will save time. Early time saving comes because your future self and collaborators will be able to find all your data, reuse and modify your code, and understand your research faster.

This applies directly to the example of working on article revisions - will you still remember all the analysis details and data nuances when your papers comes back with a request for major changes? For instance, if a colleague cannot find what data goes with which figures, there are high chances that you will also be unable to find it three years from now. In addition, itt is not uncommon to modify the design of the figures multiple times (sometimes back and forth), often modifying all figures at once.

Redoing all figures in minutes

Once a reviewer ask me to overlay individual data points onto all our 5 boxplots figures. The project was an old one, and I had not touched the data for years. Finding the right data and redo the all 5 figures would usually take ages using SPSS or excel. But since I used code, I had all figures 15 minutes later. (Note, after seeing the new figures, the reviewer agreed that the original version was better).

Later on in the project, community advantages are coming in. Data and code reusability is not only a mark of research transparency and robustness, it also means you can reuse your own code and data. It also means you can reuse code and data produced by other researchers.

The snow ball effect may be huge, and the objective of this course is to allow you to do better science in less time

Invest in data science

As an example it was estimated that research data management takes about 5% of your time, on the other hand, time lost due to poor data management is estimated to be 15%. See reference: Lowndes, J. S. S., Best, B. D., Scarborough, C., Afflerbach, J. C., Frazier, M. R., O’Hara, C. C., Halpern, B. S. (2017). Our path to better science in less time using open data science tools. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 1(0160), 1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0160

Team and community building

Data science foundations. The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia for The Turing Way Community Shared under CC-BY 4.0 License. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3332807

Data science tools will make it easier not only to collaborate with researchers in your lab, but also with researchers outside of your lab, or even with non-researchers (citizen science or software professionals). These may bring valuable expertise in the project. Being part of a collaborative community will also create impact beyond citations and papers, something which starts to be valued by funding agencies, and which make research more fun, valued and interesting.

We may also add to the pot that creating a network around your research is a critical aspect of building a career in academia. Being known as a good and skilled collaborator can open doors to many opportunities.

A journey starts

You step into the Road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there is no knowing where you might be swept off to.

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings

This training will give you some starting points, but implementating data science principles is a long and always renewed process. But you do not need to do it all at once, and you do not need to do it alone.

After the training, do not hesitate to join (or create) a community of like-minded researchers where you live (there are always some if you look). In addition, there may be people at your institution whose job is to help you. Look for data steward or data managers, research data engineers, IT support, open science büros at your institution and be pro-active contacting them. There are also almost endless online resources and helpful communities. For instance, The Turing Way guide for data science and research provides several detailed chapters to cover topics across reproducibility, project design, collaboration, communication, research ethics and community building.

The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia for The Turing Way Community Shared under CC-BY 4.0 License. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3332807

References

- A Quick Guide to Organizing Computational Biology Projects Noble WS (2009) A Quick Guide to Organizing Computational Biology Projects. PLOS Computational Biology 5(7): e1000424. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000424

- Seddighi, M, Allanson, D, Rothwell, G, Takrouri, K. Study on the use of a combination of IPython Notebook and an industry-standard package in educating a CFD course. Comput Appl Eng Educ. 2020; 28: 952– 964. https://doi.org/10.1002/cae.22273

- Mendez, K.M., Pritchard, L., Reinke, S.N. et al. Toward collaborative open data science in metabolomics using Jupyter Notebooks and cloud computing. Metabolomics 15, 125 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11306-019-1588-0

Key Points

motivations

Setting up a computational project

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

How to set up a computational project?

What main concerns and challenges exist and how to address them?

How to create a project repository for sharing, collaboration and an intention to release?

Objectives

Describe best practices for setting a project repository

Build a basis for collaboration and co-creation in team projects

Apply computational reproducibility and project management practices

Make it easy for each contributor to participate, contribute and be recognised for their work

Setting up a Project

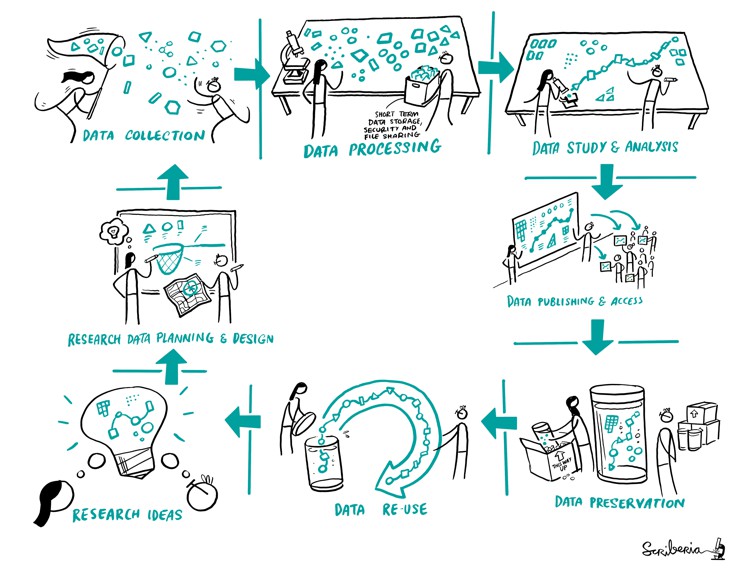

Research Lifecycle. The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia for The Turing Way Community Shared under CC-BY 4.0 License. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3332807

A research project starts right with a research idea. We start by communicating that with other researchs in our team. Then come the following steps:

- planning and designing the research work

- describing the research protocols

- deciding how data will be collected

- selecting methods and practices for processing and wrangling data

- conducting our studies and analysis

- publishing all the research objects so everybody can access it

- archiving it to ensure that our research is reusable, meaning, that someone else can go through this whole process of reproducing or building upon our work.

Each of these steps is important for every single researcher, irrespective of their roles in the project. However, a project lead (such as Principal Investigators, managers and supervisors) have an added responsibility to set up the project in a way that ensures that all members of their research team can work together efficiently at all stages of the project.

With an overarching goal to maintain research integrity and ethical practices from the start, we need to consider reproducibility methods, collaborative approaches and transparent communication processes for the research team as well as the external stakeholders. As project leads, managers and team organisers, it is crucial to be deliberate and clear about the tools and platforms selected for the project, as well as expectations from each contributor from the beginning. Dedicating some time in thinking through and documenting the setup of a project saves time, ensuring successful implementation of research plans at different stages of research. At this stage, you can’t be sure that everything will always go as planned or there will be no unexpected challenges, but it helps prepare in advance for risk management and adapt to changes when needed.

Main Concerns and Challenges

Scientific results and evidence are strengthened if those results can be replicated and confirmed by several independent researchers. This means understanding and documenting the research process, describing what steps are involved, what decisions are made from design to analysis to implementation stages and publishing them for others to validate. Research projects already start with multiple documents such as project proposal, institutional policies and recommendations (including project timeline, data management plan, open access policy, grant requirements and ethical committee recommendations), which should be available to the entire research team at all times. Furthermore, throughout the lifecycle of a project we handle experimental materials such as data and code, refer to different published studies, establish collaboration with others, generate research outputs including figures, graphs and publications, many of which undergo multiple versions. Then there is a general need to document the team’s way of working, different roles and contribution types, project workflows, research process, learning resources and templates (such as for presentation, documentation, project reporting and manuscript) for your research team.

If not planned in advance, these different kinds of information related to the project can become challenging to record, manage or retrieve – costing precious time of everyone involved and negatively affecting collaborative work in your research team.

Shared Repository to Share Information

To manage collaborative research in computational projects with mainly distributed systems (different computers, cloud infrastructure, remote team members) it is essential to provide clear guidelines on where these digital objects should be held, handled and shared. Therefore, the first step is to establish a shared digital location (centralised, findable and accessible) like a shared drive (cloud-based or organisation-hosted server space) or online repository where all project related documentation and resources can be made available for everyone in your research team. When introduced with clear guidance for how everyone in your team can contribute to keeping the shared repository up-to-date, it helps build a sense of collaboration from the start. You can use this repository also to communicate what policies are relevant for people and their work in the project; how data, code and documentation are organised; and how peer-review, open feedback and co-creation will be enabled at all stages of the project.

Versioning

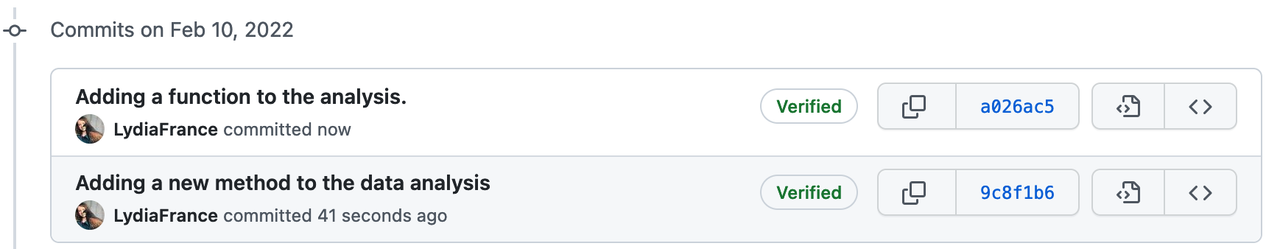

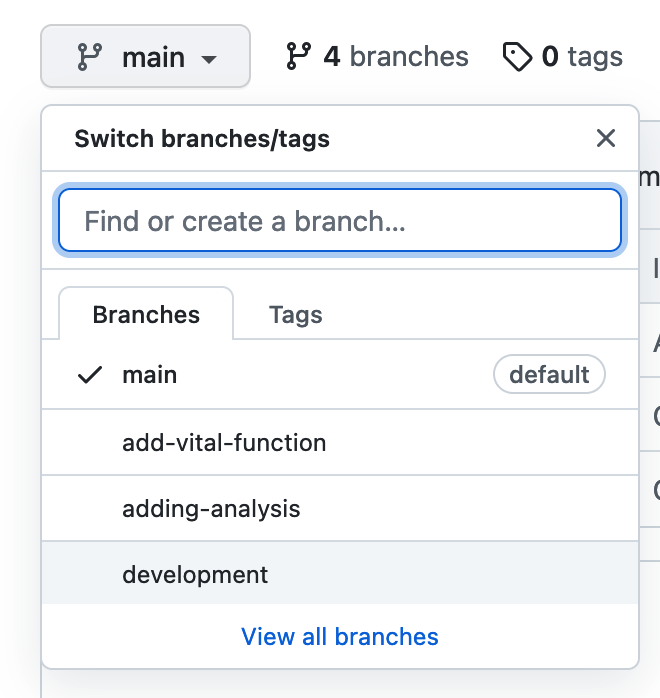

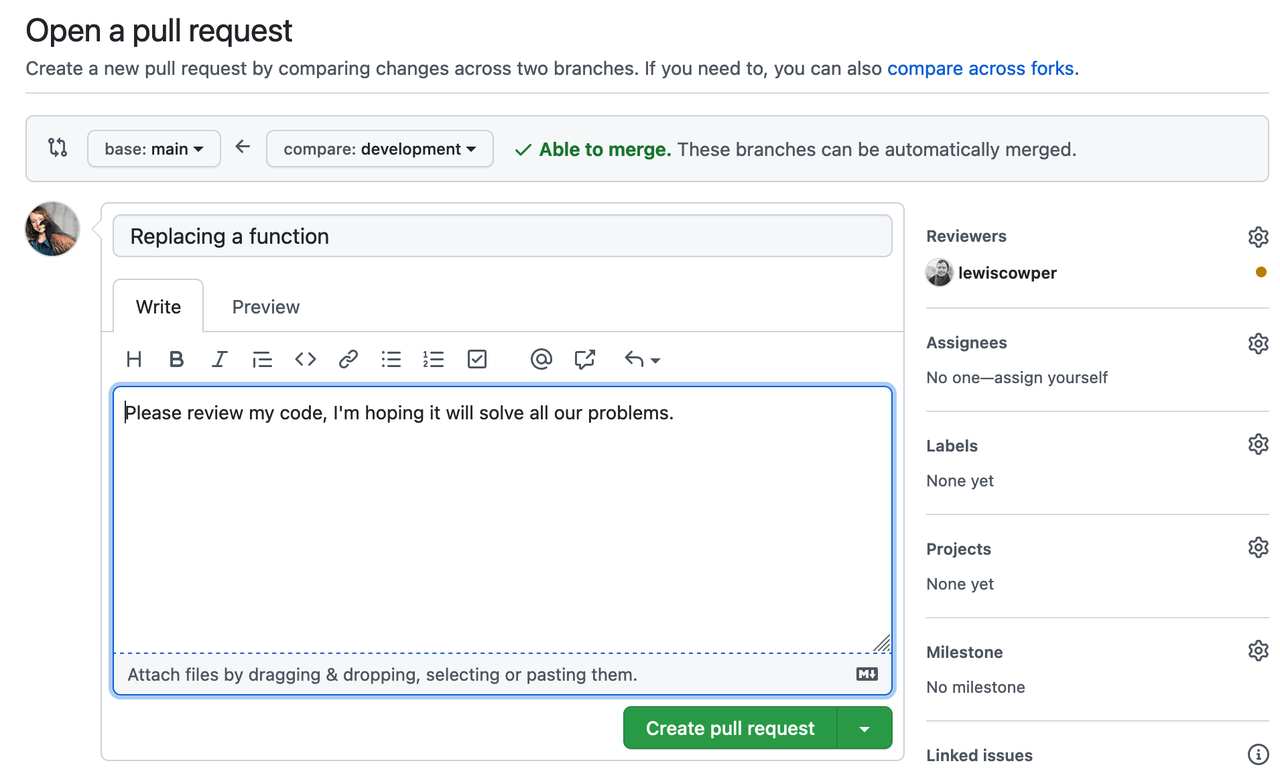

No matter how your group is organized, the work of many contributors needs to be managed into a single set of shared working documents. Version control is an approach to record changes made in a file or set of files over time so that you and your collaborators can track their history, review any changes, and revert or go back to earlier versions. Management of changes or revisions to any types of information made in a file or project is called versioning.

We have all seen a simple file versioning approach where different versions of a file are stored with a different name. Tools such as Google Drive and Microsoft Teams offer platforms to update files and share them with others in real-time, collaboratively. More sophisticated version control system exists within tools like Google docs or HackMD. These allow collaborators to update files while storing each version in its version history (we will discuss this in detail). Advanced version control systems (VCS) such as Git and Mercurial provide much more powerful tools to maintain versions in local files and share them with others.

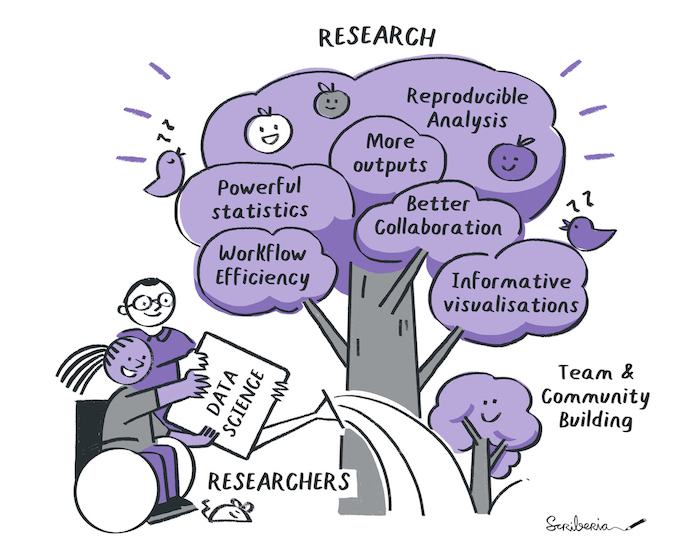

Web-based Git repository hosting services like GitLab and GitHub facilitate online collaborations in research projects by making changes available online more frequently, as well as enabling participation within a common platform from colleagues who don’t code. With the help of comments and commit messages, each version can explain what changes it contains compared to the previous versions. This is helpful when we share our analysis (not only data), and make it auditable or reproducible - which is good scientific practice. In next chapters we discuss version control for different research objects.

You can read more details in Version Control and Getting Started With GitHub chapters in The Turing Way.

Vision, Mission and Milestones

It is particularly important to share the project’s vision, mission and milestones transparently. Provide sufficient information for what the expected outcomes and deliverables are. Provide overarching as well as short-term goals and describe expected outcomes to help contributors move away from focusing on a single idea of the feature. Describe the possible expansion of the project to give an idea of what to expect beyond the initial implementation. All proposed plans for the project with information on available resources and recommended practices to ensure everyone is on the same page.

Role and Responsibilities

Create a folder/directory to give information about the different stakeholders with their roles in the project, key skills, interests and contact information (when possible). Describe what responsibilities and opportunities for collaboration different members will have. Provide resources on ways of working to ensure fair participation of stakeholders who collaborate on short- and long-term milestones within the project. It reduces or addresses concerns about the project’s progress towards meeting goals and prevent potential fallout between project stakeholders. When possible, such as in an open source project, provide these details for those outside the current group, especially when you want to encourage people outside the project to be involved.

Start with an intention to Release

- Structure and logically organise project folders and files using the consistent convention for individual file names, making them easy to locate, access and reuse.

- Review and consider how research needs to be disseminated at the end of the project as per the grant as well as institution requirements and policies.

- Choose and determine license types for different research objects such as data, software, and documentation.

- Embed computational reproducibility through skill-building in your team (see version control, computational environments, code testing, software package management).

- Add documentation process to project timelines and milestones for capturing progress, blockers and contributions by all stakeholders, making your research objects easy to attribute and release.

Choose a License

Research does not have to be completed to be useful to others. Having a license is the way to communicate how do you want your research to be used and shared. There are different types of licenses depending on the type of research objects such as code, data or documentation and preferences for re-use and sharing. The choosealicense website has a good mechanism to help you pick a license. To learn more about how to add a license to your project, read the Licensing chapter in The Turing way Guide for Reproducible Research.

Consider Computational Reproducibility

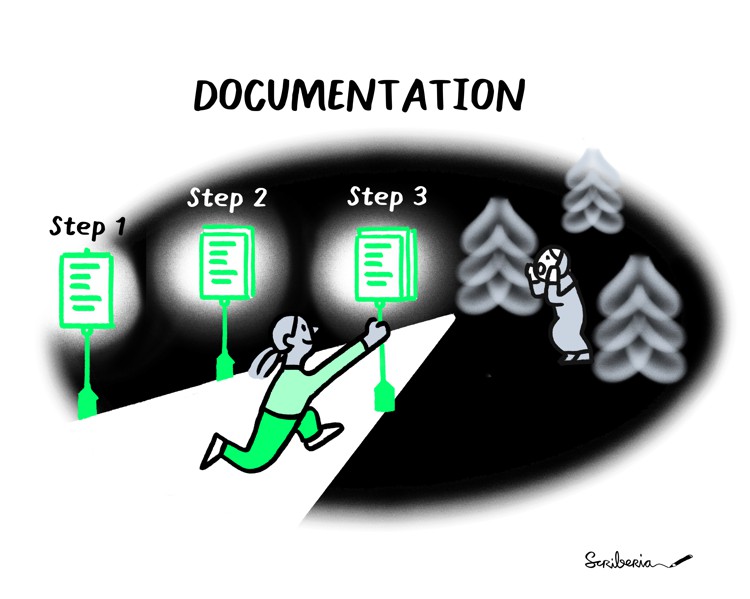

Documentation as a guiding light for people who may feel lost otherwise. The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia for The Turing Way Community Shared under CC-BY 4.0 License. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3332807

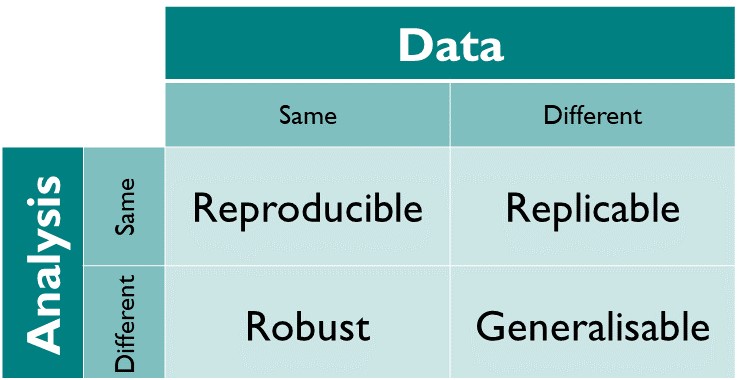

The different dimensions of reproducible research described in the matrix above have the following definitions directy taken from The Turing Way Guide to Reproducible Research (see the oveview chapter):

- Reproducible: A result is reproducible when the same analysis steps performed on the same dataset consistently produces the same answer.

- Replicable: A result is replicable when the same analysis performed on different datasets produces qualitatively similar answers.

- Robust: A result is robust when the same dataset is subjected to different analysis workflows to answer the same research question (for example one pipeline written in R and another written in Python) and a qualitatively similar or identical answer is produced. Robust results show that the work is not dependent on the specificities of the programming language chosen to perform the analysis.

- Generalisable: Combining replicable and robust findings allow us to form generalisable results. Note that running an analysis on a different software implementation and with a different dataset does not provide generalised results. There will be many more steps to know how well the work applies to all the different aspects of the research question. Generalisation is an important step towards understanding that the result is not dependent on a particular dataset nor a particular version of the analysis pipeline.

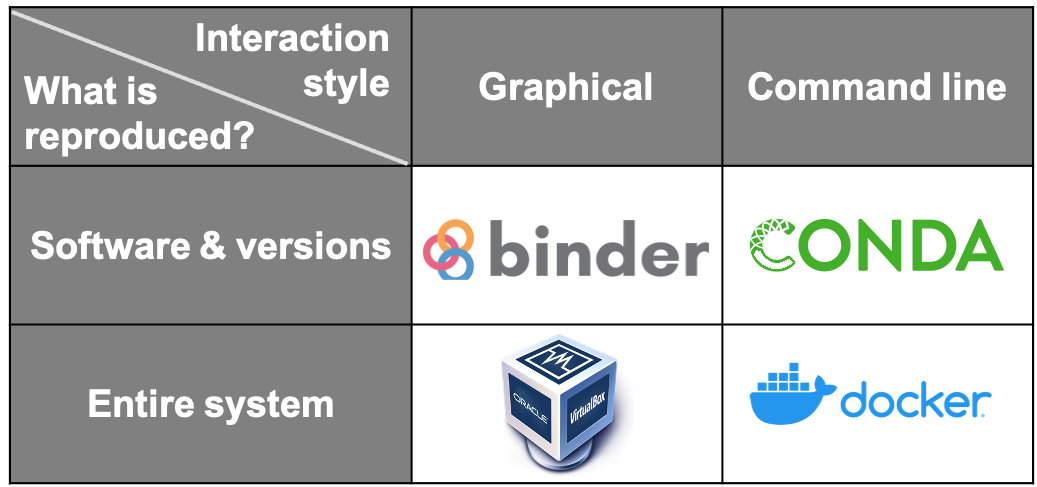

Thinking about which software, tools and platforms to use will greatly affect how you analyse and process data, as well as how you share your results for computational reproducibility. The idea is to facilitate others in recreating the setup process necessary to reproduce your research.

Some tools that can be used to enable these are the following:

- Dependency managers such as Conda keep dependencies updated and make sure the same version of dependencies used in the development environments are also used when reproducing a result.

- Containers such as Docker is a way to create computational environments with configurations required for developing, testing and using research software isolated/independent from other applications.

- Literate Programming using Jupyter Notebook is an extremely powerful way to use a web-based online interactive computing environment to execute code and script while adding notes and additional information about the application. To learn more about how to create a reproducible environment, the chapter on Reproducible Environments in The Turing way is a good place to start.

Provide a Process for Documentation

Documentation as a guiding light for people who may feel lost otherwise. The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia for The Turing Way Community Shared under CC-BY 4.0 License. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3332807

Most researchers find documentation daunting, as they think that research-related responsibilities are already overwhelming for them. It’s obvious that they see documentation as an ‘added labour’ and not important enough for carrying out a research design, implementation, analysis or publication work.

The reality is that documentation is an integral part of all research processes, from start to finish.

A systematic process for documentation is more than a formal book-keeping practice because it:

- allows everyone in your research to understand the research direction and track progress;

- adds validity to your research work when systematically built on published peer-reviewed work;

- communicates different ways to contribute, enabling diverse participation in the co-development;

- upholds practices to ensure equity, diversity and inclusion;

- recognises contributions fairly;

- gives and shares credits for all work;

- tracks the history of what worked or what did not work;

- creates transparency about early and intermediate research outcomes;

- makes auditing easy for funders, advisors or data managers;

- helps reframe research narratives by connecting different work;

- explains all decisions and stakeholders impacted by that;

- gives the starting point for writing manuscript and publication; and more!

Facilitating Documentation in your Team

NOTE

Whatever your approach is, be firm about making documentation a shared responsibility so that this job does not solely fall on the shoulders of early career researchers, members from traditionally marginalised groups or support staff.

The biggest question here is probably not ‘why’ but ‘how’ to facilitate documentation so that it is not challenging or burdensome for the team members. Here are a few recommendations to make documentation easier:

- Allocate some time at the beginning of the project to discuss with the main stakeholders of the project about what should be documented.

- Keep the tasks simple by establishing a shared repository for documentation with standard templates to guide how one should go about documenting their work (It is always easier to start with a template than an empty sheet!).

- Add documentation sprint to your project timelines and milestones to make sure that everyone is aware of their importance in the project.

- Create visible ways to recognise and incentivise the process of documenting.

Team Framework

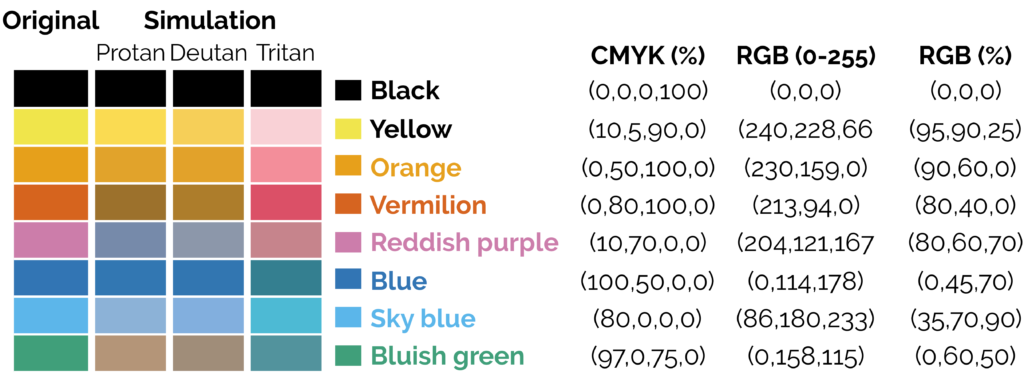

To ensure that all team members have a shared understanding of ways of working, select or adapt a Team Framework that provides guidance on how to best work in your team. For instance, Agile workflow for teamwork enables iterative development, with frequent interaction between interested parties to decide and update requirements. See Teamwork for Research Software Development tutorial by Netherlands eScience Center with lessons on teamwork, agile and scrum framework, project board such as kanban, challenges and practical recommendations.

Registered Report

After you have decided how to collect your data, analyze it and which tools to use, a good way to document these decisions is by writing a Registered Report. A Registered Report highlights the importance of the research question and the methods that will be used. They are peer-reviewed before the research, switching the focus of the review from the results to the substance of the research methods.

Conclusion

In addition to ensuring effective development and collaboration during the lifetime of the project, a well-organised project also ensures sustainability and reusability of research for both the developers and future users more dynamically. This aspect is discussed in detail in the Research Data Management episode.

Resources and References for Technical Details

- The Turing Way. The Turing Way Community. (2021). The Turing Way: A handbook for reproducible, ethical and collaborative research (1.0.1). Zenodo. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.5671094

- The Good Research Code Handbook by Patrick Mineault.

- Open Life Science training and Mentoring Programme. Batut, Bérénice, Yehudi, Yo, Sharan, Malvika, Tsang, Emmy, & Open Life Science Community. (2021). Open Life Science - Training and Mentoring programme - Website release 2019-2021 (1.0.0). Zenodo. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.5636584

Key Points

Shared repository with well structured and organised files are crucial for starting a project

Documentation is as important as data and code to understand the different aspects of the project and communicate about the research.

Licencing and open science practices allow proper use and reuse of all research objects, hence should be applied in computational research from the start.

Research Data Management

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

What is considered research data?

How to start building a research data management plan?

What is FAIR principles for data management?

Why care about documentation and metadata standards?

Objectives

Describe research data management (RDM)

Explain FAIR principles and practices for RDM

Introduce data storage and organisation plan

Discuss documentation and metadata practices

Research Data Management

Main Challenges and Concerns

Need to consider standard file formats for future use of data!

Electron Microscope Facility in our institute has produced around 5 petabytes (5,000,000 GB) of data since the institute opening. These files are stored safely and privately, and have not been standardised. As a result they are in danger of being lost forever, stored but never used. With metadata, this could form a transformative training data set for machine learning tools and possibly lead to new discoveries and insights. Creating Alpha Fold and other machine learning/AI tools you need large data sets. Meta data allows data to be future proofed for further research and even innovative research not currently possible.

Overview of Research Data Management

Research Data Management (RDM) covers how research data can be stored, described and reused. Data here is used as a generic term to encompass all digital objects. RDM is a vital part of enabling reproducible research. RDM ensures efficiency in research workflows, and also greater reach and impact, as data become FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable). Data should be stored in multiple locations and backed up regularly to prevent loss or data corruption.

Why This is Useful

Managing your data allows you to always find your data and ensure the quality of scientific practice or research. Storing your data properly and backing up regularly prevents data loss. It can help with recognition for all research outputs. It stimulates collaboration with others, who will find it easier to understand and reuse your data. RDM is cost/time efficient, as you will always be able to find and use your data.

Clearly describing data using documentation and metadata ensures that others know how to access, use and reuse your data, and also enable conditions for sharing and publishing data to be outlined.

Documentation and Metadata

Having data available is of no use if it cannot be understood. Therefore research data should always include consistent documents and metadata.

Data documentation provides contexts and full description about the data. It allows your collaborators, colleagues and future you to understand what has been done and why. Ideally written in clear and plain language, documentation describes data with sufficient information such as source, strengths, weaknesses, and analytical limitations of the data allowing users to make informed decisions when using it.

Without metadata to provide provenance and context, the data can’t be used effectively. Metadata is information about the data, descriptors that facilitate cataloguing data and data discovery. Often, metadata are intended for machine reading. When data is submitted to a trusted data repository, the machine-readable metadata is generated by the repository. If the data is not in a repository a text file with machine-readable metadata can be added as part of the documentation.

- The type of research and the nature of the data also influence what kind of documentation is necessary. It is best practice to use recognised community metadata standards to make it easier for datasets to be combined.

- The level of documentation and metadata will vary according to the project type and the range of stakeholders, including the future users.

- Examples of documentation may include items like data dictionaries or codebooks, protocols, logbooks or lab journals, README files, research logs, analysis syntax, algorithms and code comments.

- Variables should be defined and explained using data dictionaries or codebooks.

- Data should be stored in logical and hierarchical folder structures, with a README file used to describe the structure.

REMBI: Example of metadata in bioimaging data

REMBI: Recommended Metadata for Biological Images—enabling reuse of microscopy data in biology, Sarkans, U., Chiu, W., Collinson, L., Darrow, M. C., Ellenberg, J., Grunwald, D., …Brazma, A. (2021). Nature Methods, 18(12), 1418–1422. doi: 10.1038/s41592-021-01166-8

Bioimaging data have significant potential for reuse, but unlocking this potential requires systematic archiving of data and metadata in public databases. Cryo-EM and cryo-ET have proven to be powerful tools for determining high-resolution structures of biological matter and examining the functional cellular context of macromolecular complexes.

REMBI is a draft metadata guidelines to begin addressing the needs of diverse communities within light and electron microscopy. The current version of REMBI, including examples from the fields covered by the three working groups is shared online via http://bit.ly/rembi_v1.

Defining Data

Data are objects that you use and produce during your research life cycle, encompassing data sets, software, code, workflow, models, figures, tables, images and videos, interviews, articles. Data are your research asset. A good way of thinking about what might be classed as data that needs to be managed is to ask yourself the questions:

- What is the information that I need to use and write about in my paper or book?

- What information would I need to back up my conclusions?

- What information is needed by others to understand and possibly replicate the research that I have done? This information is your data.

The Research Data Lifecycle - A Model for Data Management

Research data often follows a ‘lifecycle’ that follows the research project as it evolves. This model provides a sound basis on which to plan for research data management, from data creation at the start of a research project, through to publishing and sharing research at the end of the project, and archiving any research data for the long-term and future re-use once the project has ended.

The research data lifecycle involves data creation, data use, data publication and sharing, data archiving, and data re-use or destruction. However, data have a longer lifespan than the research project that creates them. In a Data Management Plan, you can structure how you will manage and share your research data.

Data Management Plan

A Data Management Plan (DMP), or Output Management Plan, is a document that describes how your research outputs will be generated, stored, used and shared within your project. A DMP is a living document, which can be updated throughout the research project as needed.

A Data Management Plan is a roadmap for you to manage your data efficiently and securely. This can prevent data loss or breaches. Planning ahead on how to manage your data consistently can save you time later on!

A Data Management Plan should provide information on five main topics

- Roles and Responsibilities for the management of the data and code to help prevent confusion/miscommunication later in the project. Please check the DMP recommendations and requirements library research support team of your institute and the website of your funder. You can check if your funder or institute has a DMP template using DMPonline.

- A list of types, standards and formats for data, documentation and metadata (discussed later) should allow team members to understand to comply with the recommendations from the start of the project.

- A distinction can be described in the plan separately for different data types such as raw (primary), processed and ready to use (finalised to publish) datasets.

- All types of data will have to be described to be placed into context by using metadata and adequate documentation which will allow anyone in your team to interpret the data in the future.

- Data storage and backup procedures should be assessed for each project and established depending on the institutional requirements, associated costs and recommended format from your field. We will diuscuss this in detail later in this lesson.

- Preservation of the research outputs can be managed differently based on if they can be made publicly available or not. Personal data or research outputs needed to apply for patents cannot be publicly shared but they still have to be preserved for several years, depending on the policies of your country, institute and funder. Learn more about this in detail in Sharing and Archiving Data chapter in The Turing Way.

- Reuse of your research outputs should be ensured by selecting licenses for different components of your research when you make your output available on a repository (see the Licensing subchapters on data and software for more information). A dedicated document (such as a README file) is recommended for describing research outputs into context. UK Data Service has provided a Data Management Checklist to help cover different aspects of the DMP.

The FAIR Principles

The FAIR guiding principles for scientific data management and stewardship are guidelines to improve the Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability and Reusability of digital assets; all of which support research reproducibility. The FAIR principles facilitate the availability of research data so that others can reuse data.

FAIR data should be:

- Findable: The first step in (re)using data is to find them! Descriptive metadata (information about the data such as keywords) are essential.

- Accessible: Once the user finds the data and software they need to know how to access it. Data could be openly available but it is also possible that authentication and authorisation procedures are necessary.

- Interoperable: Data needs to be integrated with other data and interoperate with applications or workflows.

- Reusable: Data should be well-described so that they can be used, combined, and extended in different settings.

Making data ‘FAIR’ is not the same as making it ‘open’. Accessible means that there is a procedure in place to access the data. Data should be as open as possible, and as closed as necessary. It is also important to say that the FAIR principles are aspirational: they do not strictly define how to achieve a state of FAIRness, but rather describe a continuum of features, attributes, and behaviours that will move a digital resource closer to that goal. Even though the FAIR principles have been defined to allow machines to find and use digital objects automatically, they improve the reusability of data by humans as well. The capacity of computational systems to find, access, interoperate, and reuse data, with minimal human intervention, is essential in today’s data-driven era.

You can find a more detailed overview of the FAIR principles by GO FAIR of what the FAIR principles recommend.

Summary of “FAIR - How To”

We have provided an additional lesson to discuss the How-Tos of FAIR principles in the context of data and software. See FAIR How-To for data and software for detail.

- Reference: E. L.-Gebali, S. (2022). BOSSConf_2022_Research_Data_Management. Zenodo. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.6490583

- Deposit your data where others can find it, keep in mind where your peers can find it, such as, field specific repository and give it a stable unique identifier (PID).

- Make your data & metadata accessible via standard means such as http/API.

- Create metadata and explain in detail what this data is about, never assume people know!

- Deposit metadata with PID and make it available with/out data i.e. in case data itself is heavily protected.

- Include information on ownership, provenance and citation.

- Outline what the reusers of your data are/not allowed to do, use clear license. Commonly used licenses like MIT or Creative Commons (keep in mind funders requirements).

- Specify access conditions, if authentication or authorization is required.

- Describe your data in a standardized fashion using agreed terminology and vocabulary.

- Share the data in preferred & open file formats.

- Start the process early on!

A Note on Personal or Sensitive Data

Personal data is information about living people who can be identified using the data that you are processing, either directly or indirectly. A person’s name, address or Social Security number, as well as, racial/ethnic identity, political opinions, religious/philosophical beliefs, trade union membership, genetic and biometric data, physical or mental health, and sexual orientation are some examples of personal data. Indirect identifiers include health, economic, cultural or social characteristics. Especially when a certain combination of these identifiers can be used to identify a person, care must be taken to manage the data properly.

There are various policies in place in different countries to protect the rights of individuals over their personal data. For instance, in the European Union and the UK the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) applies to the processing of personal data and may require researchers to carry out a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA). Processing means doing anything with a person’s information, including collection, storage, analysis, sharing, deletion and destruction. Please review the national/institutional policies that apply to your research to ensure that you are up to date with the requirements of managing sensitive data. Please read Personal data management, informed consent, Research Ethics Committees Processes and Open Data sections in The Turing Way for further details.

Data Storage, Organisation and Backup Procedures

Data loss can be catastrophic for your research project and can happen often. You can prevent data loss by picking suitable storage solutions and backing your data up frequently.

- Most institutions will provide a network drive that you can use to store data.

- Portable storage media such as memory sticks (USB sticks) are more risky and vulnerable to loss and damage.

- Cloud storage provides a convenient way to store, backup and retrieve data. You should check terms of use before using them for your research data.

Especially if you are handling personal or sensitive data, you need to ensure the cloud option is compliant with any data protection rules the data is bound by. To add an extra layer of security, you should encrypt devices and files where needed. Your institution might provide local storage solutions and policies or guidelines restricting what you can use. Thus, we recommend you familiarise yourself with your local policies and recommendations.

Note

- Some concepts discussed in the previous chapter such as setting up project repository, version controlling, pre-registration, and licensing apply to this point.

- Also consider FAIR practices, data organisation and handling sensitive data practices, as well as metadata and documentation that are discussed below.

Spreadsheets, such as Microsoft Excel files, google sheets, and their Open Source alternative (for instance) LibreOffice, are commonly used by wet-lab experimentalists to collect, store, manipulate, analyse, and share research data. Spreadsheets are convenient and easy-to-use tools for organising information into an easy to write and easy to read forms for humans. However, one should use them with caution, as the use of an inappropriate spreadsheet is a major cause of mistakes in the data analysis workflow.

Please refer to the Data Carpentry Ecology Lesson and The Turing Way chapter for managing data in spreadsheet for best practices.

Backups

To avoid losing your data, you should follow good backup practices.

- You should have 2 or 3 copies of your files, stored on

- at least 2 different storage media,

- in different locations.

The more important the data and the more often the datasets change, the more frequently you should back them up. If your files take up a large amount of space and backing up all of them proves to be challenging or expensive, you may want to create a set of criteria for when you back up the data. This can be part of your data management plan (DMP).

When you are ready to release the data to the wider community, you can also search for the appropriate databases and repositories in FAIRsharing, according to your data type, and type of access to the data. Learn more about this in The Turing Way chapter on sharing and archiving Data.

Acknowledgement

- This episode is a reuse of The Turing Way chapter on Research Data Management.

- Among many authors, reviewers and contributors, we thanks Esther Plomp (Data Steward at TU Delft) for maintaining this chapter in The Turing Way Guide for Research Data Management.

- Please cite The Turing Way as: The Turing Way Community. (2021). The Turing Way: A handbook for reproducible, ethical and collaborative research (1.0.1). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5671094

Key Points

Good research data management practices esures findability of your research data.

Storing, regular backing-up and archiving prevents data loss.

Sharing all types of research data transparently makes them easier to understand and reuse by others.

Gives fair recognition to people generating, handling and using data, and further stimulates collaboration with others.

Version Control and Open Science Practices

Overview

Teaching: 10 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

How is version control system relevant for biomedical research?

How to maintain history of contributions and contributors?

How to apply open science practices to work transparently and collaborate openly?

Objectives

Describe the importance of version control systems

Nudge the use of GitHub/GitLab for open collaboration

Share open science practices for transparent and ethical research

Version Control, Open Science and Identifiers to Cite Research Objects

[Add a biological context or case study]

Maintaining History through Version Control

Version control allows tracking of history and go back to different versions as needed. The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia for The Turing Way Community Shared under CC-BY 4.0 License. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3332807

Practices and recommendations described in this lesson are applicable to all areas of biological research. What can be considered slightly different in computational projects is that every object required to carry out the research exist in digital form. Starting from research workflow, data, software, analysis process, resulting outcomes as well as how researchers involved in the project communicate with each other. This means that research objects can be organised and maintained without losing the provenance or missing knowledge of how each of these objects is connected in the context of your project.

Versioning Every Research Object

Management of changes or revisions to any type of information made in a file or project is called versioning. Version Control Systems are platform and technical tools that allow all changes made in a file or research object over time is recorded. Version Control Systems, or VCS, allows all collaborators to track history, review any changes, give appropriate credit to all contributors, track and fix errors when they appear and revert or go back to earlier versions.

Different VCS can be used through a program with web browser-based applications (such as Google Docs for documents) and more dynamically for code and all kinds of data through command-line tools (such as Git) and their integration into the graphical user interface (Visual Studio Code editor, Git-gui and gitkraken). The practice of versioning is particularly important to allow non-linear or branched development of different parts of the project, testing a new feature, debugging and error or reusing code from one project to different data by different contributors.

GitLab, GitHub, or BitBucket are online platforms that allow version-controlled projects online and allow multiple collaborators to participate. Different members can download a copy of the online repository (most recent version), make changes by adding their contributions locally on their computer and push the changes to GitLab/GitHub/BitBucket (a new version!) allowing others to build on the new development.

Read All you need to know about Git, GitHub & GitLab on Towards Data Science and version control in The Turing way for more details on workflow, technical details of using git and versioning large datasets.

Apply Open Science Best Practices

Open Science invites all researchers to share their work, data and research components openly so that others can read, reuse, reproduce, build upon and share them. Particularly in computational research and software development projects, open source practices are widely promoted. Unfortunately, making research components open doesn’t always mean that they can be easily discovered by everyone, can be reproduced and built upon by others or everyone will know how to use them. Applying open and inclusive principles to open science and reproducible research requires time, intention, resources and collaboration, which can be overwhelming for many (see Ten arguments against Open Science that you can win). However, by normalising the use of research best practices on a day-to-day basis, you can ensure that everyone has a chance to build habits around opening their work for others in the team, asking for regular feedback, getting attributed for their work and enjoying the process of collaboration.

Open doesn’t mean sharing everything, but making it ‘as open as possible and as closed as necessary’. Your research can still be reproducible without all parts necessarily being open. Research projects that use sensitive data should be more careful and follow research data management plans closely (discussed in the next chapter).

Important Reasons for Practicing Openness

Open Science in Research

- Maintains transparency

- Allows others to attribute your work fairly

- Stops others from reinventing the wheel

- Invites collaborators from all around the world

- Makes your work easy to release to be cited by others

Open versus Closed Research. The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia for The Turing Way Community Shared under CC-BY 4.0 License. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3332807

- When a project is designed in an open repository, it allows all stakeholders to track the progress, raise errors and collaborate to improve the project.

- When developed openly, such as on GitLab or through the registered report, it is easy to point to the timeline when an idea or experiment was proposed and exhibit how the project developed, who contributed and how others can attribute the work.

- Having your research open from the start can help others working in similar subjects or starting research. It allows them to conduct their review work effectively and build on the existing work, rather than starting from scratch, or ‘reinventing the wheel’.

- With open repositories and descriptions for where you need help or how others can collaborate, you can get people in your area with complementing skills and new ideas interested in your work, even when you don’t know them.

Research Objects can be Released with Digital Object Identifiers (DOI)

DOIs are alphanumerical unique and persistent identifiers with a permanent web address for different research objects that can be cited by you and other researchers. Each pre-print and publication is published with a DOI, but independent of the paper, different research objects can be published online on servers that offer DOIs at any stage of your research. Some of these servers are Zenodo, FigShare, Data Dryad (for data), Open Grants (for grant proposals) and Open Science Framework (OSF) (for different components of an open research project). It allows you to show connections between different parts of research as well as cite different objects from your work independently.

When working on GitHub for instance, you can connect the project repository with Zenodo to get a DOI for your repository. The Citation File Format, then lets you provide citation metadata, for software or datasets, in plaintext files that are easy to read by both humans and machines. Read the Making Research Objects Citable chapter in The Turing Way Guide to Communication.

Every Little Step Counts towards Openness

Open Science can mean different things in different contexts: open data, open source code, open access publication, open scholarship, open hardware, open education, open notebook, citizen science and inclusive research. Expert open science practitioners might consider applying a combination of open science practices and make decisions in their work to maintain different kinds of openness. However, for the new starters in your team, open science can be as simple as ensuring that:

- everyone has added an appropriate license to their project repository,

- recorded their work and shared their project’s roadmap on a README/landing page,

- provided some basic manual for how to use their work and how to contribute,

- given credit to previous work upon which they build, and

- regularly communicate about their research.

Small steps towards open science. The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia for The Turing Way Community Shared under CC-BY 4.0 License. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3332807

Encourage taking small steps towards openness as a responsibility towards research integrity in your team. There are many community-driven resources, guidance and opportunities in open science that provided structured support to learn about open science. For instance, The Turing Way chapter on Open Research and FOSTER Open Science provides an introduction to help researchers understand what open science is and why it is something you should care about. Another hands-on opportunity is provided by Open Life Science, which is a 16-week long training and mentoring for anyone in research interested in going through the programme to apply open science practices systematically in their research projects.

Conclusion

[What gaps have we filled in this section - add biological context]

Resources and References for Technical Details

- The Turing Way. The Turing Way Community. (2021). The Turing Way: A handbook for reproducible, ethical and collaborative research (1.0.1). Zenodo. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.5671094

- What is a Registered Report? by JMIR, referencing to Registered Reports by Center for Open Science.

- Open Life Science training and Mentoring Programme. Batut, Bérénice, Yehudi, Yo, Sharan, Malvika, Tsang, Emmy, & Open Life Science Community. (2021). Open Life Science - Training and Mentoring programme - Website release 2019-2021 (1.0.0). Zenodo. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.5636584

Key Points

Version controlled repository help record different contributions and contributor information openly.

Open Science is an umbrella term that involve different practices for research in the context of different research objects.

Online Persistent Identifiers or Digital Object Identifiers are useful for releasing and citing different versions of research objects.

Method selection

Overview

Teaching: 0 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

How can I build on existing work?

What resources/infrastructure should I consider?

Is machine learning suitable for my project?

Objectives

First learning objective. (FIXME)

Building on existing knowledge

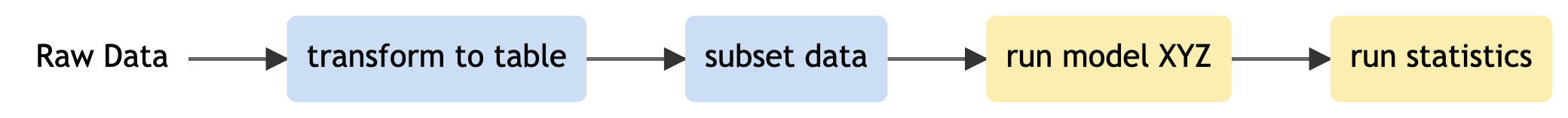

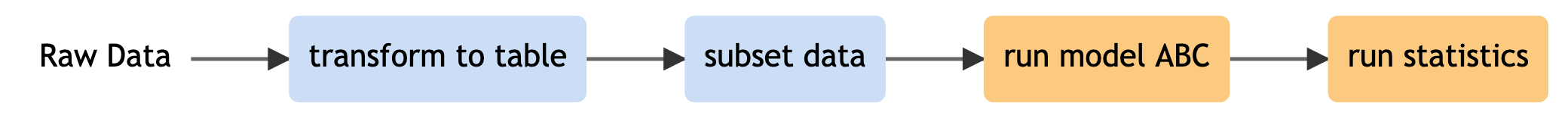

With existing code bases, downloading and using tools that exist on github is more and more valuable in the scientific community.