Implementing tools and methods

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

How to manage and oversee tasks and track progress of your projects on GitHub?

How collaborative practices help ensure code quality, testing and reuse?

What is literate programming and how does it help with early communication, testing and collaboration?

Objectives

Demonstrate GitHub Project Board to enable project management.

Discuss the importance of code quality, modular programming, and code testing for reusable error-free code.

Encourage researchers to combine code with documentation to communicate their work.

Learn about methods to capture reproducible research environments.

Project Management Tools

In the previous chapters, we have already discussed practices that enable the effective management of projects in:

- setting up shared resources;

- defining the vision, mission and roadmap of your project;

- managing data and other research-related resources; and

- versioning and tracking progress.

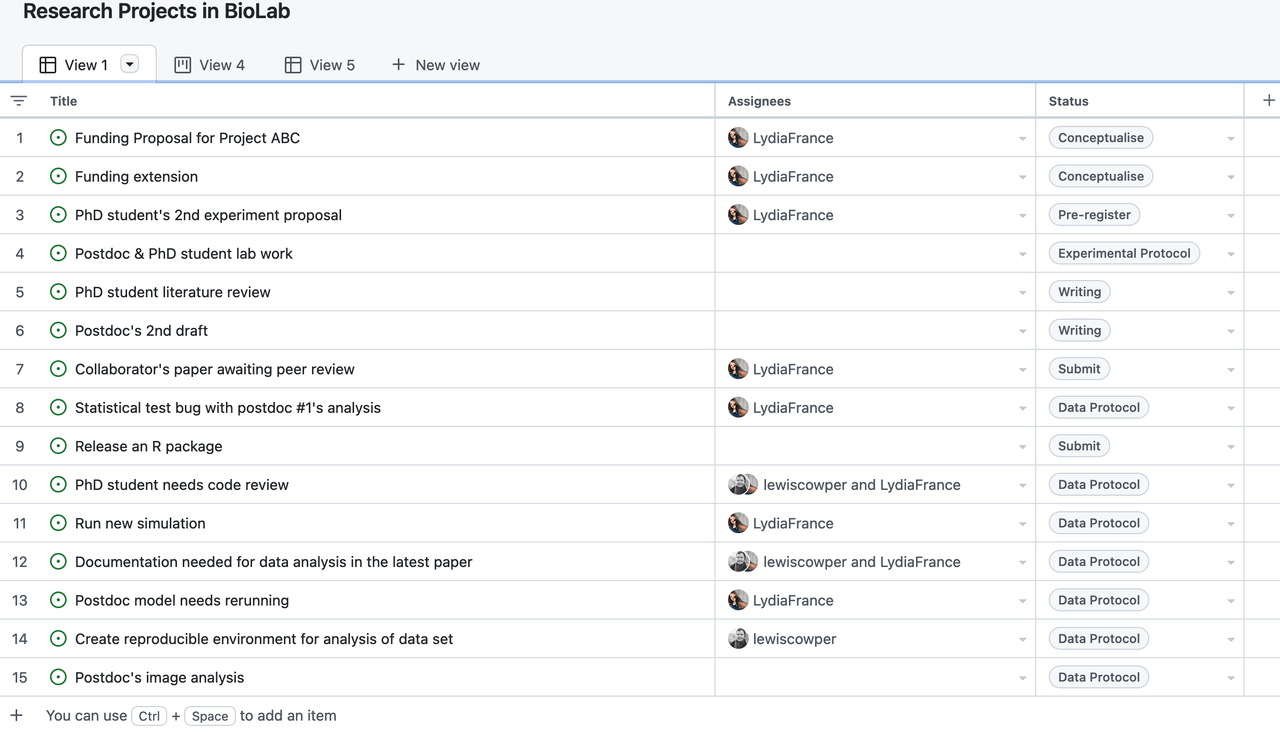

It is important to communicate tasks and responsibilities to different stakeholders of the project. However, what is even more important is to allow all members to understand where in the entire project their tasks fit and how they can track the progress of the entire project. Project management tools such as Kanban provide a visual overview of the tasks, their status (to do, in progress, done) and the people responsible for them. These tasks can be visualised on a digital board where different columns can present different statuses, different task groups or priorities.

Some tools that are popular among research community is Asana, Trello, Todoist and Notion.

For computational projects, researchers already use online repositories on Github/GitLab to store and version control their projects. They can use several advanced features on these platforms for project management.

GitHub for Project Management

Issue is a GitHub integrated feature that allows everyone to track the progress on GitHub. Similar to a ‘To-Do List’, issues can be anything from a project milestone (releasing an R package, submitting to an online data repository, a working simulation) but also specific issues with code (fixing a bug, adding a function, updating tests).

Based on the tasks described in an issue, your collaborators can address them and save or ‘commit’ changes in their local copy of the repository. Local changes then can be ‘pushed’ to the repository on GitHub for ‘review’ via the Pull Request feature. Once a pull request is opened, different collaborators can discuss and review the potential changes and add follow-up commits before those changes are ‘merged’ into the main repository.

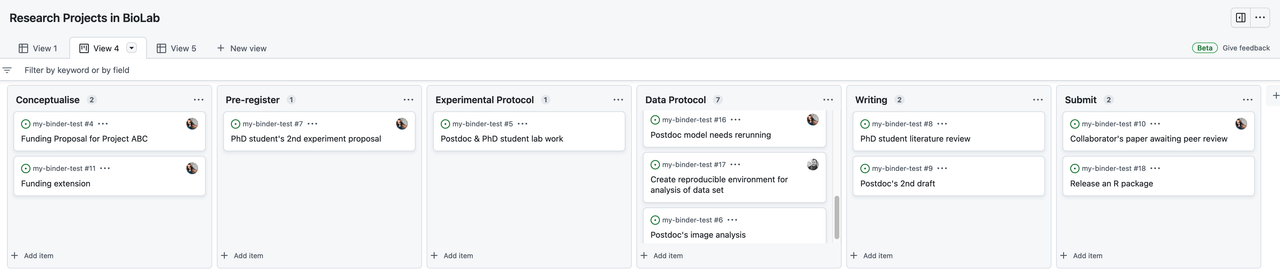

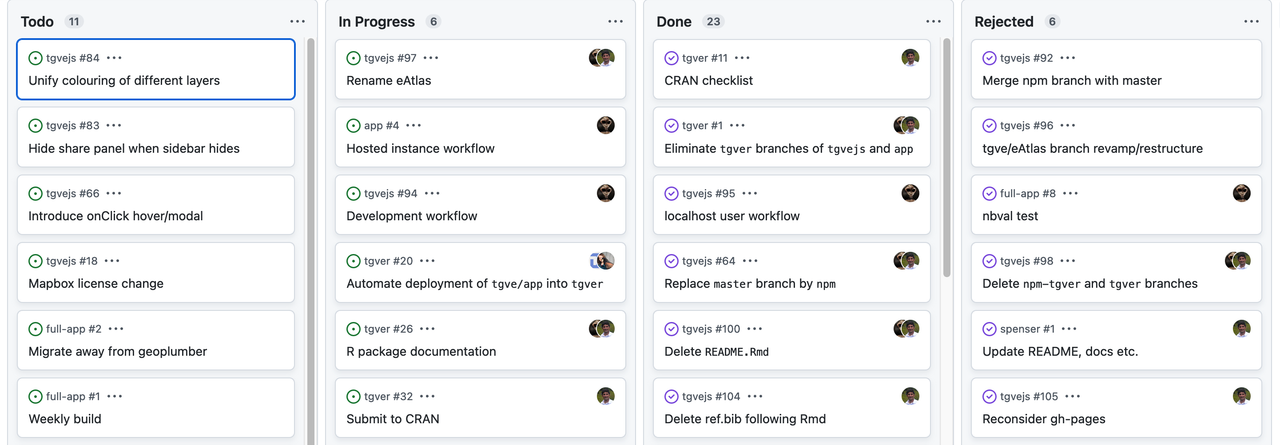

Project boards are kanban-like features on GitHub that help you visualise (list of tasks), categorise (in columns) and prioritise (drag/move around) different tasks. A collection of project boards can be created for a different set of tasks, comprehensive roadmaps, or even release checklists. By linking issues and Pull Requests, project boards can create workflows. The Project board shows metadata for issues and pull requests, like labels, assignees, the status, and who opened it. Additional notes within columns can be added as task reminders, references to issues and pull requests from any repository on GitHub.com, or to add information related to the project board. This Kanban board feature can be very helpful in getting a snapshot of multiple research projects within a team/lab and tracking what multiple people are currently working on. You can read more about Project Board in GitHub Documentation.

An example is Kanban for researcher project management. GitHub boards can be given any name.

Tutorial: Kanban Boards for Project Management (Click to view)

Collaborating on Computational Projects

Much research is now collaborative and a shared code repository can be effectively used to enable collaboration at all stages of code development at the analysis and implementation stage. Below we discuss selected research practices that allow collaboration while achieving computational reproducibility.

Code Quality

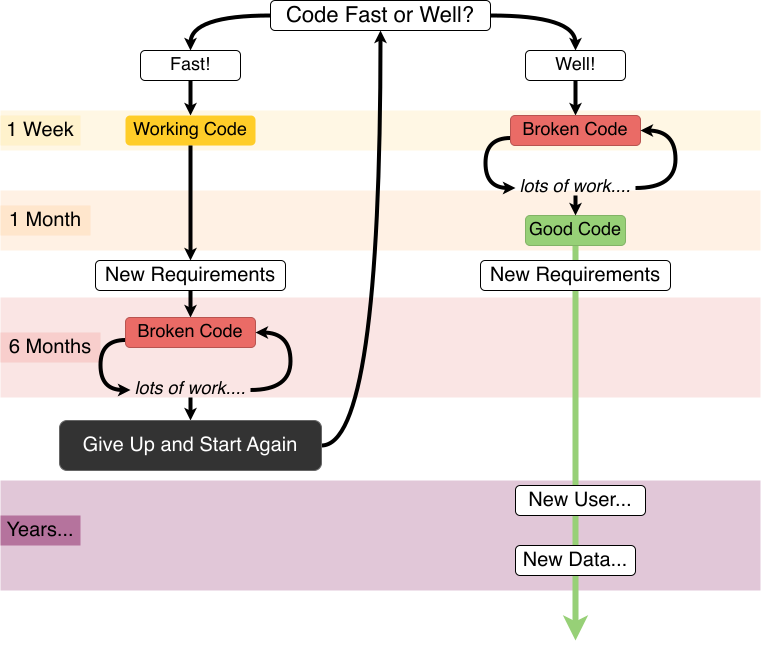

Writing code often comes down to decisions about when to save time. Code fast, and you have a solution within hours or days. Coding well requires an early investment that might be ignored in favour of “I’ll just find a quick solution…” But more often than not the time penalty is magnified as a result further down the line:

Adapted from the more pessimistic comic by XKCD

Writing good code early means losing days to deliberate good practice. But trying to undo mistakes and work with “good enough” code can take weeks or months, and still end up having to start again anyway. The blow to morale can also not be understated. “Good enough” fast code tends to have mistakes and is hard for others to review, which is not good for scientific pipelines. Even if you end up with workable code, it is not suitable for release or publication at the end of the project.

There are several ways to improve code quality that require relatively little effort. By following a coding style, code will be easier for the code developer and you (and others) to understand, even when you may not develop code yourself.

A coding style is a set of conventions on how to format code. For instance, what do you call your variables? Do you use spaces or tabs for indentation? Where do you put comments describing what the code chunk does? Consistently using the same style throughout, code becomes easier to read, understand and collaborate on even for non-coding contributors.

Opportunities where all members of a team have the chance to share examples from their work

- Cases where they found tricky bugs in their code and the process of debugging (reading error messages, tracking the bug, fixing it!)

- Project where they applied maths and statistics approaches using existing packages

- Creative visualisation of data that provides useful insights

- Tools and methods that improved their efficiency

- Code review and testing methods they learned about

These are where these time investments happen and help your students avoid the soul-destroying process of working with inefficient code and having to start from scratch. Good code is not about perfection, it is about general principles your students and postdocs can get training in. For more details, please read the Code Quality chapter in The Turing Way.

Modular Programming (Functions)

My postdoc wants to work with messy genomics data. I know my previous postdoc had to do the same thing and it took her months…. but it’s difficult to read her files so my new postdoc will have to work it out again.

Applying methods from one person’s work and applying it to another problem can take weeks, if not months, of work. Applying methods from publications is even harder: static PDF files can’t describe the lines of code and data that lead to those discoveries. This is an increasingly important problem in the face of growing mistrust in science, and a reproducibility crisis plaguing the sciences.

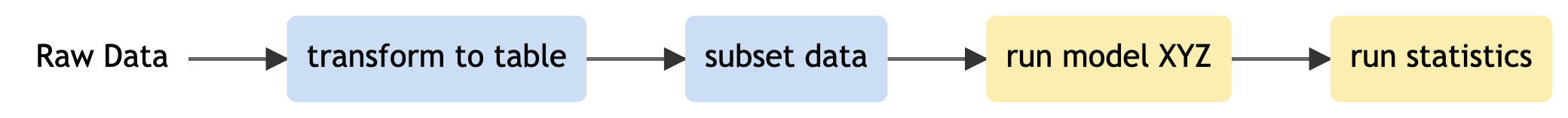

Instead, functional programming is about writing code that works as modular steps. Each step is clearly commented on and carefully produced so that it can be reused in different contexts. Often when you are analysing data, you need to repeat the same task many times. For example, you might have several files that all need loading and clean in the same way, or you might need to perform the same analysis for multiple species or parameters. Rather than copying and pasting, writing a function and calling that function leads to fewer errors and confusion overall.

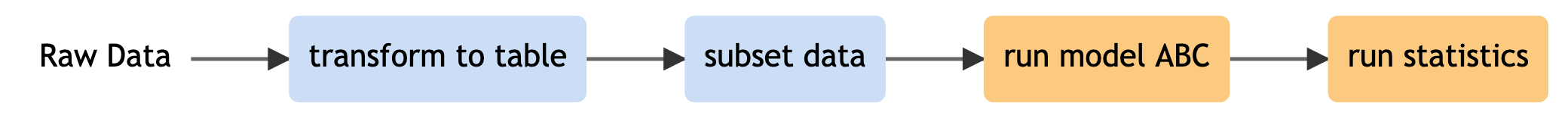

We can think of this on a broad scale, say one student’s computational work has the following steps, where blue shows data cleaning, and yellow the analysis and statistics.

Another student can take reuse the data cleaning and initial visualisation steps because her data was from the same source and is in the same format. She can later add her own model:

On the micro-scale, functional programming ensures that each code file itself is comprised of modular blocks, whether for data processing, analysis pipeline, simulation and so on. Depending on your programming language, these may be used as a package or a library or saved in files that are available for installation. Just the same as the diagram above, making sure functions are robust and reuseable means they can be shared throughout different workflows and for different projects.

Training in functional programming is usually an excellent pre-requisite for members of your lab.

A first step can be to draw out and create diagrams to plan code before starting and identifying the modular steps involved. This does not require technical knowledge of a language and is, therefore, a great exercise for direct supervision. You can find practical details on reproducible code in the Guides to Better Science by British Ecological Society.

Code Testing

You should not skip writing tests because you are short on time, you should write tests because you are short on time.

The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia. Used under a CC-BY 4.0 licence. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3332807.

The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia. Used under a CC-BY 4.0 licence. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3332807.

It is very, very easy to make mistakes when coding. A single wrong use of a character can cause a program’s output to be entirely wrong. Missing one data point, writing plus instead of minus symbol or using feet instead of meters might be a genuine human mistake, but in research, the results can be catastrophic. Careers can be damaged/ended, vast sums of research funds can be wasted, and valuable time may be lost exploring incorrect avenues. This is why code testing is vital.

Testing is a learned skill that needs to become a part of working on/improving a project. After changing their code, researchers should always check that their changes or fixes have not broken anything. There are several different kinds of testing and each has best practices specific to them.

A few important testing types

- Smoke testing: Very brief initial checks that ensure the basic requirements required to run the project hold. If these fail there is no point in proceeding to additional levels of testing until they are fixed.

- Unit testing: A level of the software testing process where individual units of a software are tested. The purpose is to validate that each unit of the software performs as designed.

- Integration testing: A level of software testing where individual units are combined and tested as a group. The purpose of this level of testing is to expose faults in the interaction between integrated units.

- System testing: A level of the software testing process where a complete, integrated system is tested. The purpose of this test is to evaluate whether the system as a whole gives the correct outputs for given inputs.

No matter the type of testing you use, general guidance is to start by writing any test and make a habit of running tests often.

- Make improvements where you can, and do your best to include tests with new code you write even if it’s not feasible to write tests for all the code that’s already written.

- Make the cases you test as realistic as possible. If for example, you have dummy data to run tests on you should make sure that data is as similar as possible to the actual data. If your actual data is messy with a lot of null values, so should your test dataset be.

There are tools available to make writing and running tests easier, these are known as testing frameworks. Find one you like, learn about the features it offers, and make use of them.

Writing tests typically encourage researchers to write cleaner, more modular code as such code is far easier to write tests for, leading to an improvement in code quality. As well as advantaging individual researchers testing also benefits research as a whole. It makes research more reproducible by answering the question “how do we even know this code works”. To gain an in-depth understanding of different kinds of tests, please see Code Testing chapter in The Turing Way.

Literate Programming

Literate programming is about comments and documentation and telling other humans what is happening in your pipeline. Depending on the scale of your computational projects, you may use one or multiple of these options:

- Inline comments when writing code (directly written in the script file)

- A README file describing what your code does

- An online documentation as a user and developer guide with step-by-step explanation

- RMarkdown or Jupyter Notebook with examples

Most of these files can be written in Markdown. Markdown is a way of writing plain text in any simple text editor that doesn’t need specific (proprietary) software to read it (no need for Microsoft Word), which can be converted to many formats including HTML, PDF or even Word documents. Many online tools including GitHub support Markdown files (.md files).

Marking up your text and code is quite simple:

**bold**–> bold_italics_–> italics- “

code snippet” –>code snippet [LINK](https://carpentries-incubator.github.io/managing-computational-projects/)–> LINK

You can do much more:

# Title(first level header)## Heading(second level header)### Subheading(third level header)(insert via a link)

See more in the MarkDown cheatsheet.

MarkDown files are however static, meaning that you can only read the files, but not execute code. R Markdown and Jupyter Notebook provide an interactive environment to work and share your code with documentation and examples for your project. For practice details about R Markdown, please see The Definitive Guide and for Jupyter Notebook, please see Jupyter/IPython Notebook Quick Start Guide.

These options are useful for communicating about the analysis workflow and results at any stage with other collaborators or the wider research community when developing open source code. Please note that sharing code in any format would require your collaborators to run and test your code locally. There are easier options to allow to run code in the browser using Binder, which we will discuss in the last lesson.

Reproducible Research Environment

Researchers’ working environments evolve as they update software, install new software, and move to different computers. If the project environment is not captured and the researchers need to return to their project after months or years (as is common in research), they will be unable to do so confidently. a computational environment is a system where a program is run. This includes features of hardware (such as the numbers of cores in any CPUs) and features of the software (such as the operating system, programming languages, supporting packages, other pieces of installed software, along with their versions and configurations).

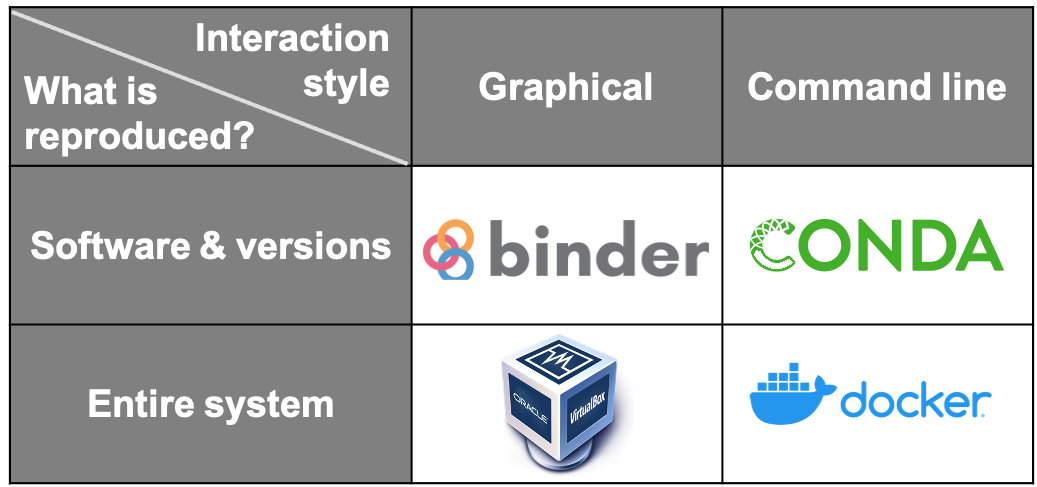

There are several ways of capturing computational environments. The major ones covered in this chapter will be Package Management Systems, Binder, Virtual Machines, and Containers. Each has its pros and cons, and the most appropriate option for you will depend on the nature of your project. They can be broadly split into two categories: those that capture only the software and its versions used in an environment (Package Management Systems), and those that replicate an entire computational environment - including the operating system and customised settings (Virtual Machines and Containers).

Another way these can be split is by how the reproduced research is presented to the reproducer. Using Binder or a Virtual Machine creates a much more graphical, GUI-type result. In contrast, the outputs of Containers and Package Management Systems are more easily interacted with via the command line. Please read more about each of these concepts and their practice use, please visit Capturing Computational Environments in The Turing Way.

Continuous integration

Continuous Integration (CI) is the practice of integrating changes to a project made by individuals into a main, shared version frequently (usually multiple times per day). CI is also typically used to identify any conflicts and bugs that are introduced by changes, so they are found and fixed early, minimising the effort required to do so. Running tests regularly also saves humans from needing to do it manually. By making users aware of bugs as early as possible researchers (if the project is a research project) do not waste a lot of time doing work that may need to be thrown away, which may be the case if tests are run infrequently and results are produced using faulty code. There are many CI service providers, such as GitHub Actions that come with their own advantages and disadvantages.

The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia. Used under a CC-BY 4.0 licence. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3332807.

The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia. Used under a CC-BY 4.0 licence. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3332807.

To learn more about different CI tools and how to use them, please read the Continuous Integration chapter in The Turing Way.

References

- The Turing Way Community. (2021). The Turing Way: A handbook for reproducible, ethical and collaborative research (1.0.1). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5671094. This episode reuses contents from the following The Turing Way chapters:

- Continuous Integration

- Code Testing

- Code Quality chapter in The Turing Way.

- Capturing Computational Environments

- The Definitive Guide

- Jupyter/IPython Notebook Quick Start Guide

- Guides to Better Science by British Ecological Society.

Key Points

Make group leaders familiar with practices that are crucial for their teams to develop reproducible code.

Encourage researchers to think about code reproducibility through quality check, testing, sharing their code as well as a research environment.

Introduce Continuous Integration for automating the testing process.

A traditional Kanban for a collaborative computational project. Keeping track of bugs and what everyone is working on.

A traditional Kanban for a collaborative computational project. Keeping track of bugs and what everyone is working on.