Setting up a computational project

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

How to set up a computational project?

What main concerns and challenges exist and how to address them?

How to create a project repository for sharing, collaboration and an intention to release?

Objectives

Describe best practices for setting a project repository

Build a basis for collaboration and co-creation in team projects

Apply computational reproducibility and project management practices

Make it easy for each contributor to participate, contribute and be recognised for their work

Setting up a Project

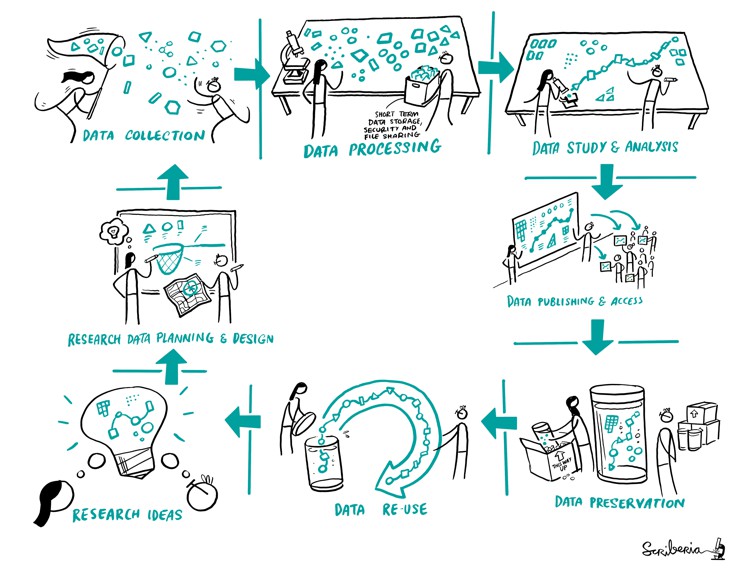

Research Lifecycle. The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia for The Turing Way Community Shared under CC-BY 4.0 License. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3332807

A research project starts right with a research idea. We start by communicating that with other researchs in our team. Then come the following steps:

- planning and designing the research work

- describing the research protocols

- deciding how data will be collected

- selecting methods and practices for processing and wrangling data

- conducting our studies and analysis

- publishing all the research objects so everybody can access it

- archiving it to ensure that our research is reusable, meaning, that someone else can go through this whole process of reproducing or building upon our work.

Each of these steps is important for every single researcher, irrespective of their roles in the project. However, a project lead (such as Principal Investigators, managers and supervisors) have an added responsibility to set up the project in a way that ensures that all members of their research team can work together efficiently at all stages of the project.

With an overarching goal to maintain research integrity and ethical practices from the start, we need to consider reproducibility methods, collaborative approaches and transparent communication processes for the research team as well as the external stakeholders. As project leads, managers and team organisers, it is crucial to be deliberate and clear about the tools and platforms selected for the project, as well as expectations from each contributor from the beginning. Dedicating some time in thinking through and documenting the setup of a project saves time, ensuring successful implementation of research plans at different stages of research. At this stage, you can’t be sure that everything will always go as planned or there will be no unexpected challenges, but it helps prepare in advance for risk management and adapt to changes when needed.

Main Concerns and Challenges

Scientific results and evidence are strengthened if those results can be replicated and confirmed by several independent researchers. This means understanding and documenting the research process, describing what steps are involved, what decisions are made from design to analysis to implementation stages and publishing them for others to validate. Research projects already start with multiple documents such as project proposal, institutional policies and recommendations (including project timeline, data management plan, open access policy, grant requirements and ethical committee recommendations), which should be available to the entire research team at all times. Furthermore, throughout the lifecycle of a project we handle experimental materials such as data and code, refer to different published studies, establish collaboration with others, generate research outputs including figures, graphs and publications, many of which undergo multiple versions. Then there is a general need to document the team’s way of working, different roles and contribution types, project workflows, research process, learning resources and templates (such as for presentation, documentation, project reporting and manuscript) for your research team.

If not planned in advance, these different kinds of information related to the project can become challenging to record, manage or retrieve – costing precious time of everyone involved and negatively affecting collaborative work in your research team.

Shared Repository to Share Information

To manage collaborative research in computational projects with mainly distributed systems (different computers, cloud infrastructure, remote team members) it is essential to provide clear guidelines on where these digital objects should be held, handled and shared. Therefore, the first step is to establish a shared digital location (centralised, findable and accessible) like a shared drive (cloud-based or organisation-hosted server space) or online repository where all project related documentation and resources can be made available for everyone in your research team. When introduced with clear guidance for how everyone in your team can contribute to keeping the shared repository up-to-date, it helps build a sense of collaboration from the start. You can use this repository also to communicate what policies are relevant for people and their work in the project; how data, code and documentation are organised; and how peer-review, open feedback and co-creation will be enabled at all stages of the project.

Versioning

No matter how your group is organized, the work of many contributors needs to be managed into a single set of shared working documents. Version control is an approach to record changes made in a file or set of files over time so that you and your collaborators can track their history, review any changes, and revert or go back to earlier versions. Management of changes or revisions to any types of information made in a file or project is called versioning.

We have all seen a simple file versioning approach where different versions of a file are stored with a different name. Tools such as Google Drive and Microsoft Teams offer platforms to update files and share them with others in real-time, collaboratively. More sophisticated version control system exists within tools like Google docs or HackMD. These allow collaborators to update files while storing each version in its version history (we will discuss this in detail). Advanced version control systems (VCS) such as Git and Mercurial provide much more powerful tools to maintain versions in local files and share them with others.

Web-based Git repository hosting services like GitLab and GitHub facilitate online collaborations in research projects by making changes available online more frequently, as well as enabling participation within a common platform from colleagues who don’t code. With the help of comments and commit messages, each version can explain what changes it contains compared to the previous versions. This is helpful when we share our analysis (not only data), and make it auditable or reproducible - which is good scientific practice. In next chapters we discuss version control for different research objects.

You can read more details in Version Control and Getting Started With GitHub chapters in The Turing Way.

Vision, Mission and Milestones

It is particularly important to share the project’s vision, mission and milestones transparently. Provide sufficient information for what the expected outcomes and deliverables are. Provide overarching as well as short-term goals and describe expected outcomes to help contributors move away from focusing on a single idea of the feature. Describe the possible expansion of the project to give an idea of what to expect beyond the initial implementation. All proposed plans for the project with information on available resources and recommended practices to ensure everyone is on the same page.

Role and Responsibilities

Create a folder/directory to give information about the different stakeholders with their roles in the project, key skills, interests and contact information (when possible). Describe what responsibilities and opportunities for collaboration different members will have. Provide resources on ways of working to ensure fair participation of stakeholders who collaborate on short- and long-term milestones within the project. It reduces or addresses concerns about the project’s progress towards meeting goals and prevent potential fallout between project stakeholders. When possible, such as in an open source project, provide these details for those outside the current group, especially when you want to encourage people outside the project to be involved.

Start with an intention to Release

- Structure and logically organise project folders and files using the consistent convention for individual file names, making them easy to locate, access and reuse.

- Review and consider how research needs to be disseminated at the end of the project as per the grant as well as institution requirements and policies.

- Choose and determine license types for different research objects such as data, software, and documentation.

- Embed computational reproducibility through skill-building in your team (see version control, computational environments, code testing, software package management).

- Add documentation process to project timelines and milestones for capturing progress, blockers and contributions by all stakeholders, making your research objects easy to attribute and release.

Choose a License

Research does not have to be completed to be useful to others. Having a license is the way to communicate how do you want your research to be used and shared. There are different types of licenses depending on the type of research objects such as code, data or documentation and preferences for re-use and sharing. The choosealicense website has a good mechanism to help you pick a license. To learn more about how to add a license to your project, read the Licensing chapter in The Turing way Guide for Reproducible Research.

Consider Computational Reproducibility

Documentation as a guiding light for people who may feel lost otherwise. The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia for The Turing Way Community Shared under CC-BY 4.0 License. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3332807

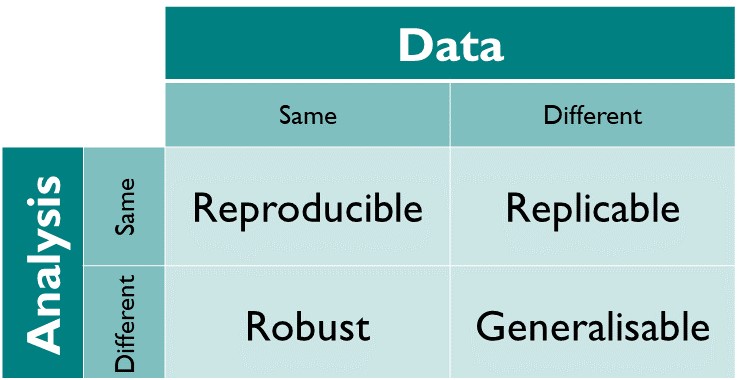

The different dimensions of reproducible research described in the matrix above have the following definitions directy taken from The Turing Way Guide to Reproducible Research (see the oveview chapter):

- Reproducible: A result is reproducible when the same analysis steps performed on the same dataset consistently produces the same answer.

- Replicable: A result is replicable when the same analysis performed on different datasets produces qualitatively similar answers.

- Robust: A result is robust when the same dataset is subjected to different analysis workflows to answer the same research question (for example one pipeline written in R and another written in Python) and a qualitatively similar or identical answer is produced. Robust results show that the work is not dependent on the specificities of the programming language chosen to perform the analysis.

- Generalisable: Combining replicable and robust findings allow us to form generalisable results. Note that running an analysis on a different software implementation and with a different dataset does not provide generalised results. There will be many more steps to know how well the work applies to all the different aspects of the research question. Generalisation is an important step towards understanding that the result is not dependent on a particular dataset nor a particular version of the analysis pipeline.

Thinking about which software, tools and platforms to use will greatly affect how you analyse and process data, as well as how you share your results for computational reproducibility. The idea is to facilitate others in recreating the setup process necessary to reproduce your research.

Some tools that can be used to enable these are the following:

- Dependency managers such as Conda keep dependencies updated and make sure the same version of dependencies used in the development environments are also used when reproducing a result.

- Containers such as Docker is a way to create computational environments with configurations required for developing, testing and using research software isolated/independent from other applications.

- Literate Programming using Jupyter Notebook is an extremely powerful way to use a web-based online interactive computing environment to execute code and script while adding notes and additional information about the application. To learn more about how to create a reproducible environment, the chapter on Reproducible Environments in The Turing way is a good place to start.

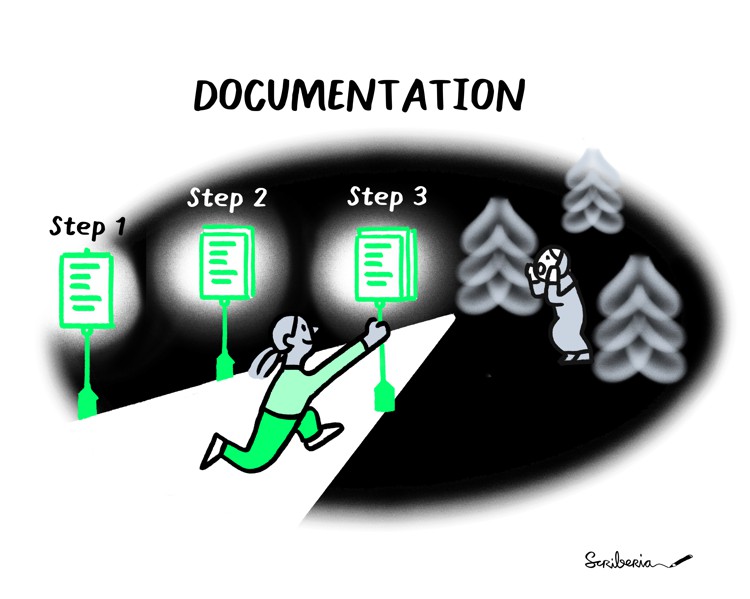

Provide a Process for Documentation

Documentation as a guiding light for people who may feel lost otherwise. The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia for The Turing Way Community Shared under CC-BY 4.0 License. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3332807

Most researchers find documentation daunting, as they think that research-related responsibilities are already overwhelming for them. It’s obvious that they see documentation as an ‘added labour’ and not important enough for carrying out a research design, implementation, analysis or publication work.

The reality is that documentation is an integral part of all research processes, from start to finish.

A systematic process for documentation is more than a formal book-keeping practice because it:

- allows everyone in your research to understand the research direction and track progress;

- adds validity to your research work when systematically built on published peer-reviewed work;

- communicates different ways to contribute, enabling diverse participation in the co-development;

- upholds practices to ensure equity, diversity and inclusion;

- recognises contributions fairly;

- gives and shares credits for all work;

- tracks the history of what worked or what did not work;

- creates transparency about early and intermediate research outcomes;

- makes auditing easy for funders, advisors or data managers;

- helps reframe research narratives by connecting different work;

- explains all decisions and stakeholders impacted by that;

- gives the starting point for writing manuscript and publication; and more!

Facilitating Documentation in your Team

NOTE

Whatever your approach is, be firm about making documentation a shared responsibility so that this job does not solely fall on the shoulders of early career researchers, members from traditionally marginalised groups or support staff.

The biggest question here is probably not ‘why’ but ‘how’ to facilitate documentation so that it is not challenging or burdensome for the team members. Here are a few recommendations to make documentation easier:

- Allocate some time at the beginning of the project to discuss with the main stakeholders of the project about what should be documented.

- Keep the tasks simple by establishing a shared repository for documentation with standard templates to guide how one should go about documenting their work (It is always easier to start with a template than an empty sheet!).

- Add documentation sprint to your project timelines and milestones to make sure that everyone is aware of their importance in the project.

- Create visible ways to recognise and incentivise the process of documenting.

Team Framework

To ensure that all team members have a shared understanding of ways of working, select or adapt a Team Framework that provides guidance on how to best work in your team. For instance, Agile workflow for teamwork enables iterative development, with frequent interaction between interested parties to decide and update requirements. See Teamwork for Research Software Development tutorial by Netherlands eScience Center with lessons on teamwork, agile and scrum framework, project board such as kanban, challenges and practical recommendations.

Registered Report

After you have decided how to collect your data, analyze it and which tools to use, a good way to document these decisions is by writing a Registered Report. A Registered Report highlights the importance of the research question and the methods that will be used. They are peer-reviewed before the research, switching the focus of the review from the results to the substance of the research methods.

Conclusion

In addition to ensuring effective development and collaboration during the lifetime of the project, a well-organised project also ensures sustainability and reusability of research for both the developers and future users more dynamically. This aspect is discussed in detail in the Research Data Management episode.

Resources and References for Technical Details

- The Turing Way. The Turing Way Community. (2021). The Turing Way: A handbook for reproducible, ethical and collaborative research (1.0.1). Zenodo. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.5671094

- The Good Research Code Handbook by Patrick Mineault.

- Open Life Science training and Mentoring Programme. Batut, Bérénice, Yehudi, Yo, Sharan, Malvika, Tsang, Emmy, & Open Life Science Community. (2021). Open Life Science - Training and Mentoring programme - Website release 2019-2021 (1.0.0). Zenodo. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.5636584

Key Points

Shared repository with well structured and organised files are crucial for starting a project

Documentation is as important as data and code to understand the different aspects of the project and communicate about the research.

Licencing and open science practices allow proper use and reuse of all research objects, hence should be applied in computational research from the start.